Sanctuary schemes support women experiencing domestic violence and children to remain safely in their home, through the implementation of a "safety framework" involving law enforcement and other community actors, while removing the perpetrator from the space. The legislative framework should protect a woman’s right to remain in the home and allow for removal of the perpetrator.

Examples of Legislation Supporting Sanctuary Schemes

In Serbia, the Family Law adopted in 2005, allows courts to issue an order for the removal of the perpetrator from family housing, and they can also order that victims of domestic violence be allowed to stay in family housing, in both cases regardless of the ownership of housing (Family Law, Article 198(2).

In Brazil, what has become popularly known as the ―Maria da Penha Law (2006) allows for the removal of the abuser from the home (Federal Law 11340, Section 2, Article 22).

In India, the Indian Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (2005) explicitly recognizes the right of women victims of domestic violence to reside in a shared household, and provides that ―every woman in a domestic relationship shall have the right to reside in the shared household, whether or not she has any right, title or beneficial interest in the same. In addition, the Act guarantees that a person suffering domestic violence ―shall not be evicted or excluded from the shared household or any part of it by the respondent [i.e. the abuser] save in accordance with the procedure established by law (The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, No 43 of 2005, Section 17).

Source: extracted from United Nations General Assembly (A/HR/C/19/53). 2011. Report of the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and on the right to non-discrimination in this context.

Sanctuary schemes are developed to address individual needs, informed by a full case-specific risk assessment covering the type and condition of the property, and the needs and circumstances of the household. They are only a reasonable option if the assessment indicates that remaining in the home or community is not too dangerous for the woman and her children.

The level and duration of support needed by women using sanctuary schemes will vary, from minimal security monitoring to intensive specialist assistance. Support needs are likely to change over time, and should be carefully monitored on an ongoing basis (i.e. at least every three months) to ensure a survivor’s safety is maintained.

Interventions should exist within a continuum of support that includes prevention, protection and judicial services.

To ensure consistency of services offered, it is important to engage and maintain a level of commitment by all staff, volunteers and core agencies. There is often high turnover within both collaborating agencies and internally, which can interrupt the effectiveness of service.

Educational campaigns can be essential in ensuring women are informed of the option to stay in their homes if they so choose and to gain community support. This can be achieved with contributions from funders, state agencies, clubs and other organizations.

Case Study: Bega Valley Staying Home Leaving Violence Project (Australia)

The Bega Valley Staying Home Leaving Violence initiative was developed as a result of the Australian government’s growing concerns over the effects of homelessness on domestic violence survivors. It aimed to reduce the risk of homelessness and trauma of relocation for domestic violence survivors; engage the community in supporting more options for all parties affected by the issue; and facilitate a collaborative partnership and coordinated strategy to improve service support to women and children. Launched in October 2004 as two-year pilot initiative supported by the New South Wales Department of Community Services and managed by the Bega Women’s Refuge, it was developed following research findings and recommendations to make the home safe for abused women and their children published by the Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse.

Results of a 2007 evaluation identified that the pilot had achieved key results related to its goals, which enabled it to continue with support from the Department of Community Services, Community Services Division. Among other outcomes:

- A majority of women (59%) reported positive benefits from the pilot, either “being able to stay safely in their homes in the long term, for an extended period or able to stay safely in the area.”

- All women reported feeling safer after participating in the pilot, noting the physical safety improvements to their home as the most effective factor.

- Community engagement was developed through a community education campaign, which presented a positive message that “the home could be made safe for women and children who had experienced domestic violence, and perpetrators could change their behaviour”. This new message was widely embraced by the community.

- The pilot promoted a number of agreements and partnerships, which formed the basis of a collaborative service provision model.

The pilot helped to identify key lessons for future models to enable women to stay safely in their homes across Australia.

Read the full Case Study.

Sources: Edwards, 2004. “Staying Home Leaving Violence”; Staying Home Leaving Violence website, 2007; Bega Valley, 2007.

Core elements of this model include:

- Working with the property owner to enhance security with specific safety measures for the residence and implementation of safety equipment, where possible, such as:

- Extra locks on exterior doors;

- Reinforced windows using bars, grills, locks, an extra layer or lamination;

- Fire retardant letter boxes;

- Smoke detectors and fire safety equipment;

- Alarms (e.g. on windows/doors, or systems connected to police or private security companies);

- Intercom equipment;

- Video entry systems;

- Security lighting, such as added external lights;

- External alterations, such as cutting trees or large plants that can be used as a hiding place, particularlyaround doors and windows; and building fences and gates to prevent entry onto the property.

- A multi-agency coordinated response that assists women to remain safe both in their homes and in the community by employing:

- Legal injunctions (such as orders of protection or restraining order that requires the abuser to move out immediately and/or to stay away from the home).

- Criminal sanctions.

- Personal alarms using Global Positioning System technology.

- Safety plans and strategies that consider ways to address risks associated with remaining in the home and community, such as:

- Creating new routes to work or school that are not known to the perpetrator and frequently changing routes so that patterns cannot be identified.

- Avoiding isolated areas/routes and minimizing travel alone after dark.

- Informing trustworthy community members such as school officials, employers, and neighbours (such as the landlord, property manager, or security officer) about the situation and safety needs, providing them with copies of restraining orders, a picture of the abuser and if relevant, their vehicle, asking them to call police if they see the abuser near the home.

- Planning for an emergency response (i.e. designating an alternative safe space to call and wait for police).

- Ensuring access to a phone during emergency situations by keeping a phone in a room that locks from the inside, or keeping a cell phone in an accessible hiding place, and programming all phones with emergency contact numbers.

- Packing a bag with all essential items needed to temporarily relocate. It is necessary and keep the bag in a safe location that is not accessible to the abuser (i.e. friend's home, work).

- Planning and practicing escape routes, including children if needed. Arranging with trustworthy neighbours to have a communication signal (such as turning a particular light on during the day) or a code word or phrase that informs them that help is needed.

- Civil remedies.

- Police support (e.g. providing information on the option to remain in the home or requesting police presence when the abuser picks up personal belongings after being ordered out of the home).

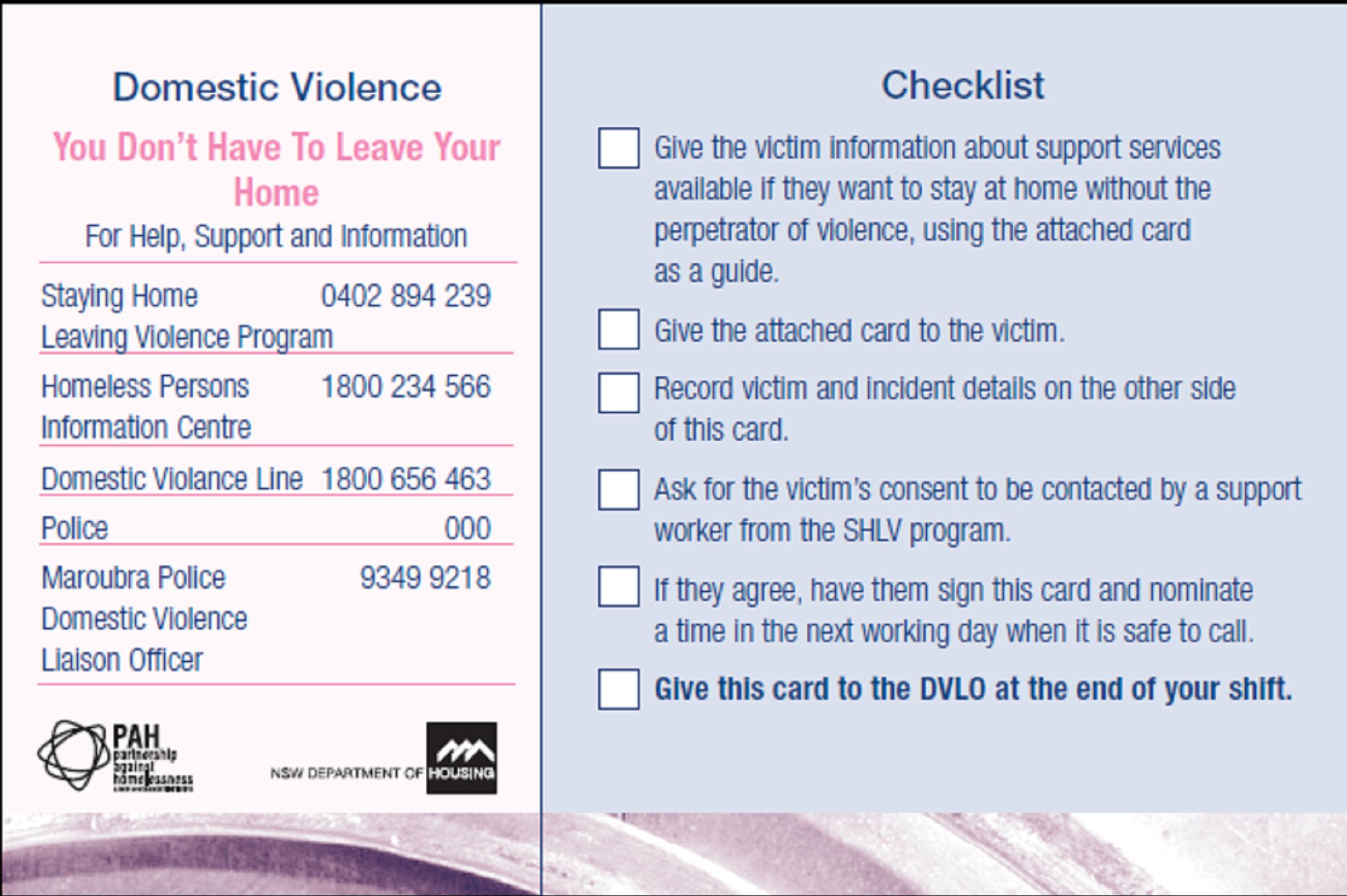

For example, in New South Wales, Australia, police are given a

checklist and information card with contact information for different service agencies, including the option to stay in their homes. This is shared with survivors when police respond to cases of domestic violence, and helps to promote appropriate and survivor-driven follow-up to incidents of abuse (Flinders Institute for Housing, Urban and Regional Research, 2008).

checklist and information card with contact information for different service agencies, including the option to stay in their homes. This is shared with survivors when police respond to cases of domestic violence, and helps to promote appropriate and survivor-driven follow-up to incidents of abuse (Flinders Institute for Housing, Urban and Regional Research, 2008). - Timely response to incidents.

- Monitoring security equipment and features to ensure they remain working. Joint planning with survivors if the sanctuary is no longer required or is no longer a safe option (i.e. identifying and preparing for shelter or other temporary accommodation).

- Joint planning with survivors if the sanctuary is no longer required or is no longer a safe option (i.e. identifying and preparing for shelter or other temporary accommodation).