- To ensure that the security sector has the operational ability to effectively respond to violence against women and girls, system-wide investments in institutional capacities, structures and processes are required, including improving skills and knowledge of personnel to respond to incidents, protect victims, and investigate and refer cases.

- Police have a critical role to play in addressing VAWG in terms of creating secure environments, responding to complaints, conducting confidential and survivor-centered interviews with alleged victims, undertaking investigations and, in some settings, appearing in court. However, poor infrastructure, lack of skills and knowledge related to VAWG among security actors, absence of sector-wide policies and protocols for addressing VAWG, and poor accountability within and across the security sector often contribute to weak capacity. In post-conflict settings there often exists an urgent need for systematic reform of the police, especially to prevent VAWG (Denham, 2008).

- Police reform is a central component to SSR. In post-conflict settings police reform should focus on how police services can better prevent and investigate crimes of violence against women and girls, provide support to survivors, and establish effective mechanisms to prevent and punish such abuses committed by police personnel (Bastick et al, 2007). Police reform strategies should aim to make the police service as a whole more gender representative, gender sensitive and more responsive to violence against women and girls.

- When implementing police sector reform related to VAWG, it can be useful to use the following guidelines and recommendations (adapted from Denham, 2008, pgs. 2 & 3, unless otherwise noted):

1. Conduct assessments and develop and monitor operational strategies

- Conduct gender-responsive assessments or audits of police services that focus specifically on gender issues related to VAWG, such as women’s recruitment in police forces, rates of sexual harassment within police forces and responses to multiple forms of VAWG.

2. Ensure gender-sensitive policies, protocols and procedure

- Develop operational protocols and procedures for assisting and supporting survivors of violence against women and girls. These should include protocols for interviewing survivors and investigating VAWG crimes, for documenting VAWG, and for referrals to health, psychosocial and legal services (Bastick et al, 2007).

- Establish gender-responsive codes of conduct and policies on discrimination, sexual harassment and violence perpetrated by police personnel. Codes of conduct and policies should be implemented with proper training, and internal (police reporting on police) and external (civilians reporting on police) accountability and oversight mechanisms should be established (Bastick et al, 2007).

- Create incentive structures to award gender-responsive policing along with respect for human rights.

- Review operational frameworks, protocols, and procedures with:

- Existing women’s police associations and other police personnel associations to identify the current situation and reforms required.

- Community policing boards, civil society organisations, including women’s groups and survivors of violence, to identify needed reforms and to ensure that protocols and procedures are responsive to community needs.

- Determine whether special measures are needed for particular groups (Bastick et al. 2007).

- Consider establishing adequately resourced women’s police stations (WPS) or specialized units on VAWG in order to encourage more victims to file complaints and improve police responses to VAWG.

- Institutionalize units as part of a system-wide approach (which includes the community level) and support them through adequate long-term investment in training and professional resources.

- Consider establishing a national governing body for the design and implementation of programmes to improve the quality of service and create standards for women’s police stations procedures and service.

- Ensure that the units are interlinked with other sectors and the overall system.

- Ensure that female officers receive proper training.

Example: Modernisation of the National Police Force of Nicaragua.

The modernisation of the National Police Force of Nicaragua demonstrates the beneficial impact of initiatives to mainstream gender and increase the participation of women. A broad range of gender reforms of the Nicaraguan police were initiated in the 1990s, following pressure from the Nicaraguan women’s movement and from women within the police. As part of a project backed by the German development organisation (GTZ), specific initiatives were undertaken including:

- Training modules on GBV within the police academies

- Women’s police stations

- Reform of recruitment criteria including female-specific physical training and the adaptation of height and physical exercise requirements for women

- Transparent promotion requirements

- Family-friendly human resource policies

- Establishment of a Consejo Consultivo de Género as a forum for discussion and investigation into the working conditions of female officers

As of 2008, 26% of Nicaraguan police officers were women, the highest proportion of female police officers of any police force in the world at that time. Nicaragua’s police service has been described as the most ‘women-friendly’ in the region, and is hailed for its successful initiatives to address sexual violence. Nicaragua’s modernisation programme has set an example for other state institutions, and a number of police forces in the region are seeking to replicate it. The reforms have helped the police gain legitimacy and credibility in the eyes of the general public: in a recent ‘image ranking’ of Nicaraguan institutions the police came in second, far ahead of the Catholic Church

Source: excerpted from Valasek, 2008, pg. 5.

Example: Sierra Leone Family Support Units (FSUs).

Sierra Leone went through a decade-long conflict where GBV was used as a strategy of war. Women and girls were subjected to abduction, exploitation, rape, mutilation and torture. In addition to crimes of war, a study by Human Rights Watch for the period of 1998 to 2000 indicated that 70% of the women interviewed reported having been beaten by their male partner, with 50% having been forced to have sexual intercourse. As the culture of secrecy began to be broken, there was a growing recognition that survivors needed access to the police to report crimes, protection in temporary shelters, treatment including medical and psychological services, and legal assistance. However, police attitudes to survivors of sexual violence were not supportive, resulting in many women not wanting to report the crimes to the police. In response, the government established the first Family Support Unit (FSU) in 2001 to deal with physical assault, sexual assault and cruelty to children. In addition, training was provided to police officers on how to handle domestic and sexual violence

Source: excerpted from Denham, 2008, pg. 18.

Example: Measures to counter human trafficking- Kosovo.

Human trafficking and prostitution exploded in Kosovo after the 1999 war. Women primarily from the former Soviet bloc countries of Moldova, Romania, Ukraine, Bulgaria and Russia were tricked and/or forced into becoming sex slaves in brothels run by various organised crime families. The presence of international peacekeeping forces, as well as other international personnel, contributed to the demand for trafficked women. Some international personnel were directly implicated in trafficking rings. The Kosovo Police Service (KPS), which was formed with the support of the UN and the OSCE, has been characterised by a high degree of gender-sensitivity. The KPS targeted women and ethnic minority applicants for recruitment. As of January 2010 women comprised 14.77 percent of the KPS. In 2009, 75 sergeants, 27 lieutenants, five captains, four majors, two lieutenant colonels, two colonels and one departmental general director were women. NATO and UN police were initially responsible for anti-trafficking, but the KPS gradually took over this responsibility. KPS officers, who received specialised training from UN counterparts such as the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), started to participate in intelligence gathering, investigations, raids and counter-trafficking operations. An Anti-Trafficking Unit focuses on prevention, protection and prosecution, and has officers in all six regional headquarters and at headquarters. The Anti-Trafficking Unit, in collaboration with the Domestic Violence Unit, has created proactive mechanisms to combat trafficking and has ensured that anti-trafficking is a priority item on police and political agendas

Source: adapted from DCAF, 2011, Gender and Security Sector Reform Examples from the Ground, pgs. 7 & 8.

3. Ensure a mechanism is in place to vet security personnel for histories of VAWG, including domestic violence

- Establish a vetting mechanism in order to ensure that police, military, and judicial personnel against whom allegations have been made of having perpetrated acts of VAWG – including domestic violence - and other serious crimes, cannot be recruited into the security forces. Vetting mechanisms have the following potential positive impact:

- (Re)-establishment of civic trust

- (Re)-legitimization of public institutions

- Facilitation of criminal prosecutions, truth telling, reparations for survivors, and other forms of institutional reform

- Enabling condition of other transitional justice measures

- May fill the impunity gap by providing a partial measure of non-criminal accountability

- Deterring acts of sexual violence by members of the security sector.

(Adapted from International Center for Transitional Justice)

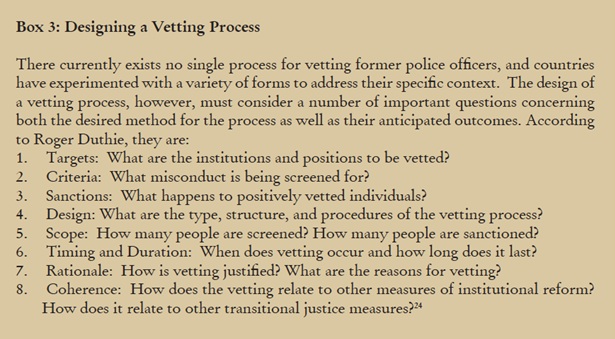

- Vetting mechanisms will differ depending on the country and context. Consider the following questions when designing a vetting mechanism in post-conflict settings:

Source: Kumar, S. and Behlendorf. B. 2010. “Policing Best Practices in Conflict / Post-Conflict Areas,” p. 17.

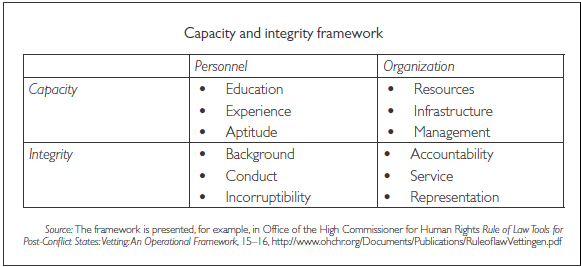

- Consider capacity and integrity as key qualities required of police personnel to fulfill the technical requirements of their work and to act in accordance with human rights, professional, ethical and rule-of law standards. The Capacity and Integrity Framework (CIF) below can provide a basis for considering these key qualities for new recruits (UNHCHR, 2006):

- Ensure that special attention is paid to seniority in rank and responsibility and to individuals publicly known to have committed gross violations of human rights. It will be important to single out those whose authority might influence the implementation of a personnel reform process. (MONUSCO, 2009. “Concept Note and Plan of Action Security Sector Reform (SSR) and Sexual Violence.”)

Example: Vetting of Police Personnel in Liberia.

The 2003 Accra Comprehensive Peace Agreement that facilitated the end of the conflict in Liberia made provisions in Article VIII for the reform of the Liberian National Police (LNP) and other security services. A number of LNP officers were selected to assist the international team with the assessment of ‘vettees’, in particular guiding international staff around neighbourhoods of Monrovia and provincial towns to validate individual records and collect complaints against, or endorsements for, those applying to join the new police force. Around 3,000 personnel were vetted. Of these, around 2,200 failed on the basis that they lacked the required educational qualifications, were too old, were physically unfit, were dead, and/or had committed human rights violations during the conflict, possessed criminal records, or simply did not exist. Retraining began for the remaining 800, a core that would be boosted by a major recruitment drive to raise the number of LNP personnel to 3,500.

The public was directly engaged in the vetting process through the media, ongoing public debates, and the publication of candidates’ photographs. The public was also encouraged to make complaints against individuals deemed to be unsuitable for police service. The vetting process took two years and has received mixed reviews. There is some concern that now that the vetting and recruitment process has come to an end, the original vetting functions will be abandoned. Indeed, achieving durability of systems in Liberia has proved a difficult task in all sectors. In addition, observers note the existence of major problems within the LNP, such as endemic corruption, poor leadership, and lack of knowledge on how operations should be based on human rights requirements and Liberian law. Moreover, there continue to be allegations that a number of police officers within the retrained force of 800 are implicated in human rights violations.

There are fears that no allegations surfaced during the vetting process because members of the public were afraid of possible retaliation as a consequence of weak measures for the protection of the identity of informants. Lessons learned from Liberia illustrate the complexity of the vetting process. Planning a vetting programme needs to take into account the structure of the vetting procedure to ensure a long-term legacy that inter alia:

- Improves integrity within the police system,

- Protects original vetting decisions, and

- Ensures the maintenance of professional standards

Source: adapted from International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ): The Legacy of Four Vetting Programs: An Empirical Review (2009).

Additional Tools

Justice as Prevention: Vetting Public Employees in Transitional Societies (Mayer-Rieckh, A. and de Greiff, P.(eds.) for International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ). 2007). New York: Social Science Research Council. This is a collection of essays systematically exploring vetting practices in a variety of countries and contexts. Avaialble in English.

Rule-of-Law, Tools for Post-conflict states – Vetting: An Operational Framework (Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). 2006) This tool includes the development of vetting mechanisms for state institutions. Available in English.

Policing Best Practices in Conflict / Post-Conflict Areas (Kumar, S. and Behlendorf, B., 2010). Strategies adopted to counter seven key policing problems faced by Afghanistan. This study addresses many of the policing challenges currently facing Afghanistan, and highlights broad solutions drawn from other contexts to reform and re-legitimize the police. Available in English.

Policing Best Practices in Conflict / Post-Conflict Areas (Kumar, S. and Behlendorf, B., 2010). Strategies adopted to counter seven key policing problems faced by Afghanistan. This study addresses many of the policing challenges currently facing Afghanistan, and highlights broad solutions drawn from other contexts to reform and re-legitimize the police. Available in English.

4. Ensure training on gender and issues related to VAWG for all security sector personnel

- Integrate gender training and issues related to VAWG – including sexual harassment – into basic training and into the curriculum of in-service training for active duty police personnel involving all levels of police officers, and including civilian staff. The aim of gender training is to enable the participants to understand the different roles and needs of women and men and to challenge discriminatory behaviour in their daily work. Gender training can enhance the capacity of security sector personnel to respond to the needs of the entire community but most specifically to provide them with the awareness, knowledge, practical skills and techniques required to prevent and respond to VAWG (DCAF, OSCE/ODIHR, UN-INSTRAW, 2008, p. 1).

- Where possible, consult with local LGBTI NGOs to explore and identify methods of integrating issues of gender identity and sexual orientation into gender trainings and issues related to VAWG. The aim of including this perspective in gender trainings is to enable participants to understand, challenge, and more effectively respond to instances of discrimination and violence against sexual and gender minorities.

- Training on VAWG should aim to increase knowledge and raise social awareness, create attitudinal change and build capacity to respond to VAWG. The curriculum will vary according to participants’ prior exposure to gender issues, operational needs and context. It is important to target senior ranking officers as well since changing attitudes must be done institutionally to be effective and sustainable (DCAF, OSCE/ODIHR, UN-INSTRAW, 2008, p. 2). Topics might include:

|

Training on VAWG |

|

|

Aim |

Potential Topic |

|

Increase knowledge and social awareness raising

|

|

|

Police attitudinal change and sensitization

|

|

|

Capacity building for response to VAWG

|

|

- Consider establishing new training and educational units that can play a pivotal role in strengthening weak police organizational structures in post-conflict settings.

- Ensure that the trainers and facilitators are qualified and well prepared:

- Consider involving women's civil society organizations in gender training activities for police personnel both in the design and implementation. These organizations may bring specific technical expertise to gender training and their involvement in police training can help to build trust between the community and the police (adapted from Bastick et al, 2007).

- Reach out to experts such as United Nations Police Officers (UNPOL) who are deployed at the same time as military personnel in most peacekeeping operations or as advisers to UN special missions. UN Police Officers help promote peace and security in many countries by supporting the reform, restructuring and rebuilding of domestic police and other law enforcement agencies through training and advising. They develop community policing in refugee or internally-displaced persons camps, they mentor and in some cases train national police officers, they provide specialization in different types of investigations and in a number of countries they help law enforcement agents to address transnational crime. In some missions, UN Police Officers are directly responsible for all policing and other law enforcement functions and have a clear authority and responsibility for the maintenance of law and order. As a result, they have become highly specialized and continue to develop tools and trainings relevant to policing in post-conflict settings. (United Nations Policing).

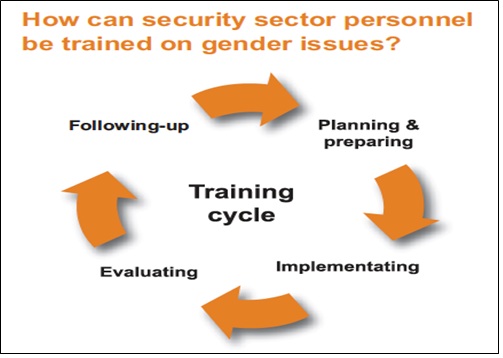

- Monitor and evaluate trainings, and use the results to improve future training and resources, as shown in the diagram below. Changing the culture of an institution requires long-term goals and planning: ‘one-off’ trainings will not change the culture of an institution. Ongoing and specialized trainings are required. (For information on basic training tools on gender and VAWG, see Section VI: Staff Training and Capacity Building.)

Source: DCAF, OSCE/ODIHR & UN-INSTRAW. 2008. “Gender Training for Security Sector Personnel (Practice Note 12),” pg. 3. Eds: Megan Bastick, Kristin Valasek.

Example: Gender dimensions of establishing the PNTL – East Timor.

The Policia Nacíonal de Timor-Leste (PNTL) was established by the United Nations on 10 August 2001. The United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) was initially given the mandate to “develop a credible, professional and impartial police service”. UNTAET focused largely on personnel recruitment and training. Following the UNTAET phase, the UN extended the scope of the reform to include capacity building in human resources management, finances, community relations and field training. From the outset, gender concerns were on the agenda in developing the PNTL. One of the first requirements established, for example, was that at least 20 percent of PNTL recruits were to be women. Addressing gender-based violence was identified early on as an urgent need. UN police statistics in December 2001 counted gender-based violence as the most commonly recorded crime in Timor-Leste.

During the initial period of the development of the PNTL, UNTAET elaborated standard operating procedures for domestic and gender-based violence cases. Building the capacity of police officers to interview victims of sexual abuse received priority attention. The PNTL training programme lasts for three months (in the Police Academy) and is followed by a three to six month long Field Training Program. UN agencies (including UNIFEM, UNDP and the Gender Affairs Unit of the UN mission) and external trainers conduct training on human rights, gender, children’s rights and gender based violence. UNTAET set up a Vulnerable Persons Unit (VPU) in March 2001, which eventually became a network of VPUs, one in each of the 13 districts.

The VPUs are part of the PNTL Criminal Investigations Unit and mandated to deal with issues of rape, attempted rape, domestic abuse (emotional, verbal and physical), child abuse, child neglect, missing persons, paternity and sexual harassment. The VPUs represent an effort to bring such crimes into the realm of the formal justice system rather than the traditional justice system. VPUs are staffed by both PNTL and UN police. VPU officers receive 17 days of additional training to fulfil their special role. Sustained efforts have been made to include female police officers in all VPUs to interview female victims, as well as female UN police officers to support the VPUs. The VPUs have also received support from the respective Gender Affairs Units of the UN missions and other UN agencies, and have co-operated with East Timorese women’s organisations and the Association of Men Against Violence (adapted from DCAF, 2011, pgs. 7 & 8).

Additional Tools

For more information on training tools, see the Security Module.

Also see:

United Nations Criminal Justice Standards for United Nations Police (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations, 2010) This handbook collates the main human rights standards applicable to policing. Available in English.

Training Curriculum of Effective Police Responses to Violence against Women (UNODC and Department of Peacekeeping Operations, 2010). The present training curriculum is designed to help develop within local and national police the knowledge and skills required to respond in an effective and appropriate manner to violence against women—specifically violence within intimate relationships. Available in English.

The Family Support Unit Training Manual. See in particular “Module 6: Domestic And Gender Based Violence (Sierra Leone Police/Ministry of Social Welfare, Gender and Children’s Affairs, 2008). This ten-module training manual is an improved version of the training manual on Joint Investigation of Sexual and Physical Abuse in Sierra Leone that had been originally developed by the FSU. It provides an overview of the requisite professional skills applicable to the work of the Sierra Leone Police and personnel of the Ministry of Social Welfare, Gender, and Children’s Affairs [MSWGCA] who happen to be core partners within the FSU. Available in English.

Responding to Violence Against Women: A Training Manual for Uganda Police Force. (Alal, Y./Kampala: Centre for Domestic Violence Prevention (CEDOVIP), 2009). The handbook is co-published by Center for Domestic Violence Prevention (CEDOVIP) and The Uganda Police Force (UPF), and provides background information on the problem of domestic violence as an abuse of human rights within our communities and provides guidelines on how to interview the victims, children who are affected by domestic violence as both victims and witnesses, and the perpetuators of domestic violence. Available in English.

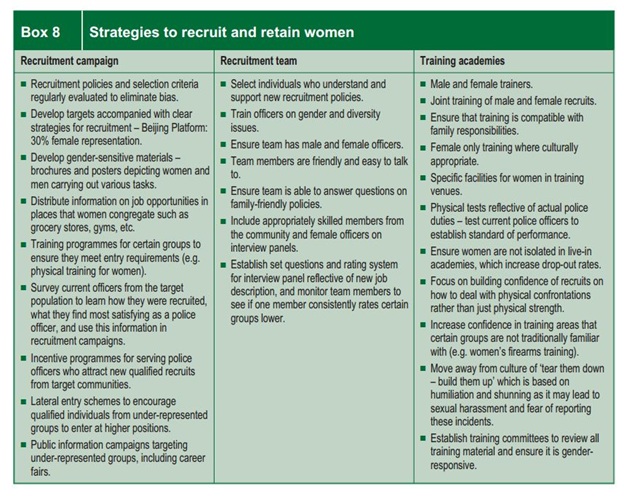

5. Ensure recruitment, retention and advancement of female personnel

- Develop an organisational culture that promotes gender equality within security services (Bastick et al. 2007)

- Consider establishing strategic targets for female recruitment and retention

- Update recruitment policies and practices to ensure they are attracting a full range of qualified individuals, including from under-represented groups.

- Update job descriptions to accurately reflect the skills required in modern policing.

- Revise and adapt human resources policies to ensure they are non-discriminatory, gender-sensitive and family-friendly.

- Establish female police associations and mentor programmes.

- Review job assessment standards and promotion criteria for discrimination. Implement performance-based assessment reviews.

- Ensure equal access to job training for career advancement (excerpted from OSCE/ODIHR, INSTRAW, DCAF, 2008, p. 3).

Excerpted from Denham, T. 2008. ”Police Reform and Gender,” pg. 12. In Bastick, M. and Kristin, V. (eds.) Gender and Security Sector Reform Toolkit. Geneva: DCAF, OSCE/ODIHR, and UN-INSTRAW.

Example: The Liberian National Police’s female recruitment programme.

The rebuilding of the Liberian National Police (LNP) commenced in 2005, after the end of Liberia’s fourteen-year-long, devastating war. During the war, the LNP had committed serious human rights violations and thus acquired a poor reputation among the population. The United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) designed a “vetting/de-activisation programme” to purge the LNP of its most brutal elements, which led to the enrolment of a new crop of police recruits. In addition, UNMIL developed a Gender Policy as part of the reform and restructuring of the LNP, the first such policy in UN peace operations.

UNMIL set a 20 per cent quota for women’s inclusion in the police and armed forces, and the LNP established a Female Recruitment Programme. The lack of educational qualifications among potential female recruits posed a challenge. The Programme selected 150 women to attend classes to receive their high school diplomas. These women, in return, promised to join and serve in the LNP for a minimum number of years.

Affirmative action of this kind expanded the pool of female police recruits without having to lower essential qualifications. A boost to recruitment of women in the Liberian police has also come from India. In January 2007, the UN’s first all-female peacekeeping contingent, made up of 103 Indian policewomen, was deployed in Liberia. During the month following their deployment, the LNP received three times the usual number of female applicants.

See a video.

Source: adapted from DCAF, 2011, Gender and Security Sector Reform Examples from the Ground, pgs. 7-8).

For additional information on recruitment, see the Security Module.