Qualitative approaches provide contextual, in-depth information on the “why” and “how.” Qualitative information complements and provides greater insight into quantitative data. It is extremely useful for understanding community level norms and attitudes underlying violence against women, the non-quantifiable factors that affect service providers’ responses to cases of violence, including stigma and discrimination, and the barriers and challenges faced by women in accessing services and support.

Challenges and limitations of qualitative methods

- Qualitative participatory methods require more time and resources

- Qualitative data is harder to analyze and compare

- Qualitative data is sometimes less “credible” to policy makers and donors who prefer numbers

Interventions aimed at addressing attitudes and beliefs in particular should balance quantitative data with qualitative approaches in their monitoring and evaluation plans.

For example, quantitative data might reveal the number of cases of violence against women reported to the police. Qualitative methods and participatory discussions with women and front-line police officers can provide critical insight into factors impacting the number of reports or lack thereof.

They might highlight for example, a lack of familiarity with rights and obligations set forth in law, the perception that police are unresponsive to survivors’ needs, the fear that if a woman brings a case to trial, she will be stigmatized in her community, thrown out of her house, or subjected to further violence, or discomfort with having to recount experiences with violence in a public setting or to officials that are insensitive.

Case Study: Strengths and Challenges Found in Participatory Research In Melanesia and East Timor

Participatory processes used to study the violence against women situation in Melanesia and East Timor proved to be effective for gaining understanding of ongoing efforts to address the issue in the region and to stimulate dialogue and critical reflection among diverse sectors of the population. In particular, some of the benefits of this approach included:

- Diversity. Through the use of participatory methods, comparable views from diverse stakeholders (i.e. Supreme Court Justices and Ministers of Women’s Affairs to women’s rights activists and local NGOs, community men and women, and traditional leaders) could be obtained. The use of similar methods across the groups enabled the researchers to identify points of commonality as well as divergent views.

- Triangulation. The use of a variety of data collection methods (document review, individual interviews and focus group discussions), informants (diversity of ethnicity, education, profession, gender, etc.) and researchers allowed for triangulation of the data to corroborate and validate the findings.

- Participation. Engaging key stakeholders in each country from the very beginning of the process was critical for gaining access to a broad range of informants. Including these stakeholders in the interpretation of findings and the development of recommendations created a sense of local ownership of the results. The resulting regional report had much more legitimacy as a blueprint for action than it would have, if it had been viewed simply as the work of external consultants, or a donor agency.

- Dialogue. The participatory process provided a neutral ground for dialogue among some sectors that rarely interacted, and in the consensus-building process around the recommendations, some compromises were reached that might not have been achieved in other circumstances. Most importantly, it allowed for the voices of less powerful groups, particularly women survivors of violence, to be heard throughout the process.

The main challenges found in using a participatory approach, included:

- More time and resources than a traditional evaluation were needed

- Comparison and synthesis of a large amount of complex data from five different countries

- Building consensus around the results among participants from wildly different backgrounds and perspectives

In the end, most participants agreed that the value of the final report lay, not in the recommendations, but in the process leading up to them – a demonstration of social change through research.

Source: Ellsberg, Bradley, Egan and Haddad. 2008 Using Participatory Methods for Researching Violence against Women: An Experience from Melanesia and East Timor

Methods for collecting qualitative data include

- Pre/post intervention focus group discussions with target populations

- Pre/post intervention interviews with target populations and key informants

- Participatory methods such as, participatory learning and action and participatory action research

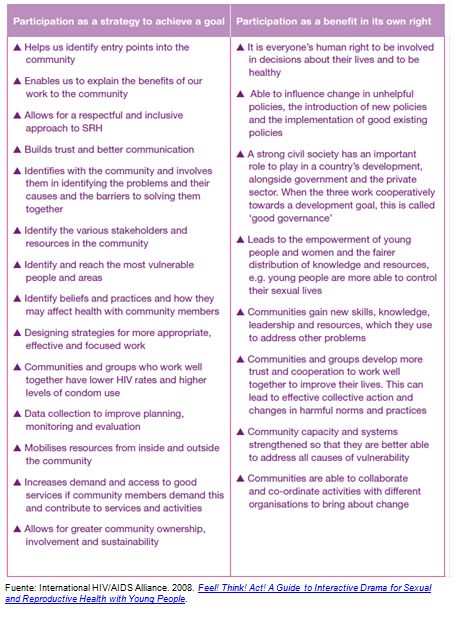

Participatory Learning and Action and Participatory Action Research include a range of methods that emphasize the full participation of local communities as a way of learning about specific needs, challenges and opportunities, and identifying appropriate action for addressing concerns. These techniques use community members’ knowledge and experience as a point of reference, engaging in participatory discussion to stimulate group reflection and motivate participants to act collectively. Individual and collective empowerment of participants and community level social transformation are explicit goals of participatory learning and action and participatory action research and the techniques are particularly useful if the main objectives are social change or the transfer of skills. If accuracy of data is critical, a more traditional approach to research may be more appropriate.

The main principles of participatory research are that:

- It involves a flexible, interactive process of exploration that stimulates creativity, flexibility and improvisation in the use of methods to facilitate learning.

- Community members direct the process, in the sense that knowledge is produced on the basis of their own experiences. Community members also define the priorities of the research, as well as the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

- The role of outsiders is to facilitate rather than direct the learning process and the production of knowledge.

- Participants, not just the researchers or external agents, own the methods and the results. The socialization of knowledge and techniques in participatory research is greatly encouraged.

- Diversity is enhanced rather than averaged out. Participatory research attempts to reveal differences between situations, attitudes, and practices according to social class, gender, and ethnicity and tries to learn from cases that apparently do not conform to the expected.

- Triangulation is used to validate results. This refers to the use of different methods for studying the same phenomena, or using the same method with groups that represent diversity, for instance by gender and class, to see whether results are valid for each group.

- The entire process, not just the results, is designed to enhance empowerment of individuals and communities, thereby stimulating social change. Emphasis is placed on assessing the quality and understanding the impact of participation, rather than just promoting participation

Examples of Selected Participatory Methodologies

There are a number of qualitative, participatory methods including: focus group discussions, open-ended stories, Venn diagrams, timelines, photovoice/digital stories, body mapping, census mapping, social mapping, problem and solution trees, community stakeholder mapping, role-plays, case studies, brainstorming sessions, ranking of priorities, force field analysis and so many more. Below are examples of some of these methodologies. Additional descriptions can be found in the resources section.

Open ended stories

(Ellsberg and Heise, 2005)

Open-ended stories are useful for exploring people’s beliefs and opinions, and for identifying problems or solutions while developing a programme. The method is especially appropriate for use with people with less formal education, and helps stimulate participation in discussions.

In an open-ended story, the beginning, middle, or ending of a relevant story is purposely left out. The audience discusses what might happen in the part of the story that is missing. Usually, the beginning tells a story about a problem, the middle tells a story about a solution, and the end tells a story of an outcome.

To use this technique, consider the following:

- It is important to design the whole story in advance, so that the part that is left out “fits” the complete story. A storyteller with good communication skills will be needed. Depending on the amount of group discussion, telling the story and filling in the missing part may take as long as two hours.

- The storyteller must be able to tell the story, listen, and respond to the community analysis. Using two facilitators can help—one to tell the story and one to help the community fill in the “gaps.” The story and the response need to be captured. Tape recording can be helpful in this instance.

Example of Open-ended Stories: Forced Sex among Adolescents in Ghana

In Ghana, investigators used a version of the open-ended story technique to discover ways in which adolescents say “no” to sex if they do not want to participate and what would happen if the adolescents tried to use condoms.

By learning how young people react in such situations, the team hoped to refine its health promotion materials to better support healthy sexual behaviour. In this adaptation, investigators used a storyline approach in which participants role play a story based on a scene described by the facilitator. At appropriate moments, the facilitator cut into the story to elicit discussion and to introduce a new element or “twist” that might change people’s reactions.

The storyline technique created a relaxed and entertaining atmosphere for young people to act out and discuss issues of sexuality and abuse in a nonthreatening atmosphere. The stories allowed participants to discuss an issue without necessarily implicating themselves in the situation. To help animate the characters in the minds of participants, the facilitators solicited input from the group about the names, traits, and personality of the characters. Following is an example of one of the stories used to discuss forced early marriage:

Alhaji married Kande with her parents’ blessing. Kande (meaning the only girl among three boys) is 14 years old and Alhaji is 50 years old. Alhaji has three wives already but none of them gave birth to a son. So one day he calls Kande and discusses his problem and his wish of getting a son from her. He also tells her that since she is a virgin, she will by all means give birth to a boy. Kande gets frightened and tells him that she is too young to give birth now. She also assures him that if he can wait for two more years, she will give him a son. Alhaji replies, “I married you. You can’t tell me what to do. Whether you like it or not, you are sleeping with me tonight.” After the drama sketch was played out, the facilitator asked the group if they thought the story was realistic and if similar situations happened in their area. After analyzing their data, the authors noted, “These stories seemed to show that, at least among these participants, coercion, trickery, deceit, force, and financial need are well known and all too common elements of sexuality for youth in Ghana.”

Source: Tweedie I. Content and context of condim and abstinence negotiation among youth in Ghana. In: Third Annual Meeting of the International Research Network on Violence against Women. Takoma Park, Maryland: Center for Health and Gender Equity; 1998. P. 21-26. As cited in Ellsberg and Heise, PATH 2005.

Example of adapting an open-ended story: Rosita goes to the health clinic

In the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) review of gender-based violence services in Central America, the story of Rosita was adapted to talk to health workers about how women living with violence are treated in the health center. The story ends when Rosita goes to the health center for a routine visit and the nurse asks her whether she has ever been mistreated by her husband. The group is asked to imagine how the story ends through a discussion of the following questions:

- What will Rosita tell the nurse when she asks about violence?

- How will Rosita feel when she is asked about violence?

- How does the nurse feel about asking Rosita about her family life?

- What will happen to Rosita if she admits what is happening to her at home?

- What type of help would be most useful to her?

- Do you think she will receive this help at the health center?

- Is Rosita’s situation common for women in this community?

- What happens when women come to this health center asking for help with domestic

violence situations?

These questions were used to introduce a more focused discussion on the type of services offered to women in Rosita’s situation in the participants’ health center. The story stimulated a very rich discussion of how providers detected violence in their clients, and how they treated them.

Examples of providers’ comments follow:

“I used to treat women with muscle spasms all the time and I never asked them by questions. Then I started to realize that many of these cases were due to violence. Women are waiting for someone to knock on their door; some of them have been waiting for many years…They are grateful for the opportunity to unload their burden.”

“Sometimes taking a Pap smear, I’ll see older women with injuries, dryness and bruises from forced sex.”

Source: Velzeboer M, Ellsberg M, Clavel C, Garcia-Moreno C. Violence against Women: The Health Sector Responds. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization, PATH; 2003.

Open ended stories were also used in the assessment of interventions in Melanesia and East Timor to get a sense of women’s experiences with violence and with the accessibility and quality of services for survivors/victims. Through two stories of fictional women—one beaten by her husband, and another involving her younger sister who was raped by a schoolmate—this study explored the types of support to which women might have access in Melanesia and East Timor. The stories were presented during focus groups discussions and participants were asked where these women would go for help, what kinds of barriers they would encounter, and what would be the likely outcomes of their efforts.

Example of responses to open-ended stories used in Melanesia and East Timor

Women overwhelmingly seek the support of informal networks first. Formal services, such as women’s centres or the police, are used only as a last resort, for various reasons. When responding to the story of Laila, the battered wife, participants said she might turn to her friends or family for immediate shelter; however, neither would be able to help for long. Laila’s friends might fear becoming involved, including because she may fear reprisals from her own husband. The family might feel the husband had a right to beat Laila, particularly if a bride-price had been paid. They might worry about being forced to return the bride-price to the husband’s family. Also, given that customary law in several countries gives custody of children to the husband’s family, the wife might lose her children if she separates. “When this happens, the father would tell the children that their mother ran away because she did not like them. Children suffer when their mother is not there” (local court clerk, Vanuatu).

Because domestic violence is seen as a private matter, participants said other community members or relatives would be unlikely to intervene to protect Laila from her husband. Mi no wantem save (‘I don’t want to know’ in Bislama) and Ino bisnis blo mi (‘It’s not my business’ in Bislama) are phrases commonly used by those who witness violence but do not intervene to stop it

Laila might also seek the support of the local chief or church pastor. The pastor would remind Laila that she vowed to stay in her marriage ‘till death do us part’, and would encourage her to ‘forgive and forget’ and return to her husband. “If the case is in the rural area, then [the] Fiji Women’s Crisis Centre is too far and so pastors are usually the first stop. In some villages, the pastors can continue to visit them and counsel them based on biblical principles….” (Social worker, Social Welfare Department, Labasa, Fiji).

The chief, on the other hand, might set up a kastom court meeting, in which the husband or both the husband and Laila would pay a fine before the chief sent Laila back to her husband. Most women come to realize, as a result, they can do very little about the violence. “She cannot speak out because of bride-price is one [reason] and secondly she is under threat.… Part of the reason is she has no place to go back, like her father and mother they do not want her, which happens to some women. And some they have a lot of children and they can’t go back. So they have their own reasons (Women’s focus group discussion in Kup Papua New Guinea). (Australian Agency for International Development, 2008)

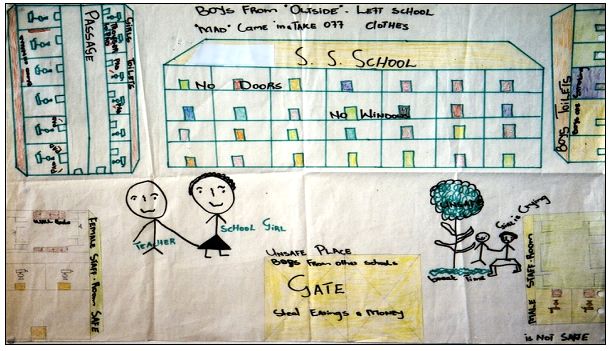

Community mapping

A community map is an excellent tool for collecting qualitative data, especially in cultures that have a strong visual tradition. As with many other participatory techniques, maps can be created on paper with colored pens or constructed in the dirt, using natural materials such as sticks and pebbles. Mapping can be used to identify or highlight many aspects of a community, including geographic, demographic, historic, cultural and economic. With respect to violence against women and girls, community mapping can be used to identify for example, the number, locations and quality of various services (medical, legal, shelters and others) available to survivors; or the high-risk areas where abuse, sexual harassment and assaults are likely to occur on the way to-and-from work, school or in other public spaces. (Ellsberg and Heise, 2005)

How-to approach community mapping:

1. The community was visited and community members were invited to participate:

2. The purpose of the visit was introduced and people’s interest and availability to participate was assessed.

3. Participants were requested that someone draw a map of the desired area.

4. Some people will naturally reach for a stick and begin drawing on the ground. Others will look around for paper and pencils. Have materials ready to offer, if it is appropriate.

5. As the map is beginning to take shape, other community members will become involved. Give people plenty of time and space. Do not hurry the process.

6. Wait until people are completely finished before you start asking questions. Then interview the visual output. Phrase questions so that they are open-ended and nonjudgmental. Probe often, show interest, let people talk.

7. If there is additional information that would be useful, you may ask focused questions once conversation about the map has finished.

8. Record any visual output, whether it was drawn on the ground or sketched on paper. Be accurate and include identifying information (place, date, and participant’s names if possible).

(CARE International, 1998)

Community Mapping of Sexual Violence from the Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya

CARE, an international non-profit organization, used community mapping as part of its rapid assessment of sexual violence in the Dadaab refugee camps on the border between Kenya and Somalia. Participants were asked to make a map of the camp community and to identify areas of heightened risk for women. The women identified several key areas where they did not feel safe:

(1) The bushes around the community well, where attackers lie in wait for women;

(2) The camp’s western border, where bandits can easily enter through weakened sections of the live thorn fences; and

(3) The hospital, where women line up before dawn to collect coupons guaranteeing them access to the health center later in the day.

This exercise allowed NGO organizers to identify ways to improve women’s safety.

Source: Igras S, Monahan B, Syphrines O. Issues and Responses to Sexual Violence: Assessment Report of the Dadaab Refugee Camps; Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: Care International; 1998. As cited in Ellsberg and Heise, 2005.

Community Mapping of Sexual Violence in Schools in South Africa

Researchers in Cape Town, South Africa, asked high school girls to draw a map of places where they felt unsafe. The map showed that the girls considered the most unsafe places to be:

(1) The gates of the school, where former students would come to sell drugs and harass students;

(2) The toilets, which in addition to being filthy were places where girls could be harassed by gangs; and

(3) The male teachers’ staff room, where teachers would collude to send girls for errands so that other teachers could sexually harass or rape them during their free hours.

The girls were so afraid to go near the staff room that they arranged always to do errands in pairs so as to be able to protect each other.

Source: Abrahams N. School-based Sexual Violence: Understanding the Risks of Using School Toilets Among School-going Girls. Cape Town, South Africa: South African Medical Research Council; 2003. As cited in Ellsberg and Heise, 2005.

Source: Abrahams N. School-based Sexual Violence: Understanding the Risks of Using School Toilets Among School-going Girls. Cape Town, South Africa: South African Medical Research Council; 2003. As cited in Ellsberg and Heise, 2005.

Community mapping is also an excellent tool for getting perspective on the kinds of services that are available in a particular community, where they are located, and what challenges women may face in accessing them. Maps can be used to pinpoint the location of police stations, shelters and safe houses, clinics, counseling and testing centers, and other services, and serve as a framework for understanding any barriers and obstacles preventing women from utilizing them. These might include for example, the fact that a clinic or testing center is located in a visible, public location (and therefore lacking adequate anonymity to ensure privacy and safety; police stations and courthouses are located miles away from a woman’s house and from other services, and are not accessible by public transportation; or shelters are located right next to where the perpetrator lives or works.

In the United Kingdom, the Equality and Human Rights Commission and the End Violence against Women Coalition have developed an online mapping of survivor services available across Britain. The Map of Gaps highlights the disparities in availability of services in order to advocate for women survivors’ equal access to the services they may need in situations of abuse. The services mapped, include: general violence against women services, domestic violence services, women’s refuges (safe spaces/ shelters), services for ethnic minority women, perpetrator programmes, specialist domestic violence courts, sexual violence services, rape crisis centres, sexual assault referral centres and prostitution, trafficking and sexual exploitation services. View the maps.

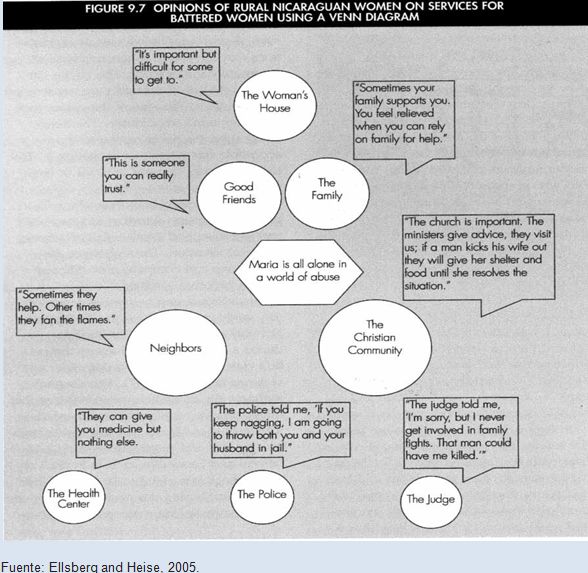

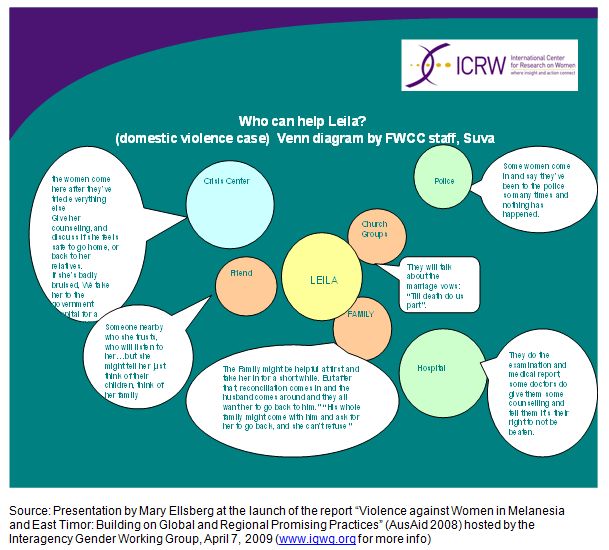

Venn diagrams

Venn diagrams, also known as circular or “chapati” diagrams, are useful for analyzing social distance, organizational structures, or institutional relationships. The facilitator draws circles of different sizes to represent individuals or organizations that are linked to the problem or community under study. The size of the circles indicates the person, organization or service delivery point’s importance. The item’s location on the sheet represents how accessible the item is for the person or community. The colors can be used to highlight positive or negative perceptions or relations with the given entity. The technique may be used in small or large groups. (Igras, Monahan and Syphrines, 1998)

Another method is to make two diagrams per group—one that indicates the real situation and another that represents the ideal situation. Through these diagrams, one can compare how different groups perceive a subject.

Using a Venn Diagram to Obtain Opinions of Nicaraguan Women on Services for Survivors of Domestic Violence

Rural Nicaraguan women in a participatory study carried out by the Nicaraguan Network of Women against Violence produced a Venn diagram to assess the public’s view of the proposed domestic violence law. The diagram indicates the individuals or institutions that might be able to help “Maria,” a woman whose husband beats her. The circles indicate by size and proximity to Maria how helpful and accessible each individual or institution is perceived to be to her. The text accompanying the circles illustrates the views expressed by women in the group.

Venn diagrams of people and services women might turn to for assistance from an assessment of interventions in Melanesia and East Timor

Different qualitative methods can be used together. The Venn diagram below in conjunction with Leila’s open-ended story presented earlier provide a more complete understanding of her experience and the support mechanisms available to her.

Photo Voice and Digital Stories

The photo voice and digital stories techniques, also known as shoot back, are an excellent method for participatory research. These techniques provide recorded documentation of first-person accounts on a particular topic. They are created by community members using text, voice-over, photographs, video, drawings and music. These approaches are used worldwide on a variety of topics, including domestic violence, rape, other sexual assaults and harassment. (Ellsberg and Heise, 2005)

The steps in the process include:

(Wang, 1999 as cited in Ellsberg and Heise, 2005)

- Conceptualize the problem.

- Define broader goals and objectives.

- Recruit policy makers as the audience for photo voice findings.

- Train the trainers.

- Conduct photo voice training.

- Devise the initial theme/s for taking pictures.

- Take pictures.

- Facilitate group discussion.

- Allow for critical reflection and dialogue.

- Select photographs for discussion.

- Contextualize and storytell.

- Codify issues, themes, and theories.

- Document the stories.

- Conduct the formative evaluation.

- Reach policymakers, donors, media, researchers, and others mobilized to create change.

- Conduct participatory evaluation of policy and programme implementation.

Similar to any and all research techniques where individuals are directly involved, the participant's well-being is the primary and central concern in the process of making digital stories. Sensitivity, clarity and accountability for facilitator, narrator and viewer are important and can be achieved by:

- Recruiting participants on a voluntary basis who understand the process and implications of participation. Narrators can be recruited from partner agencies or organizations responding to a specific need, and can include, for example, women or girl survivors accessing services, educators and advocates.

- Ensuring informed consent and the option for participants to opt-out of the process at any time.

- Ensuring the product emerges out of a participatory media production workshop in which: Participants work closely with a team of trainers on content, image and other aspects of the final video and participants are empowered through hands-on assistance with editing, computers, etc. to produce their own products.

In addition, it is good practice to accompany the videos with a detailed discussion guide for facilitators that addresses the videos in an ethical, human-rights based and gender-sensitive manner. These guides can include various components, such as:

- Guidance on a wide variety of topics, ranging from self-examination to choosing a discussion method;

- Story summaries and transcripts;

- Key points to address;

- Discussion questions, both general and story-specific;

- A story-subject index; and

- Websites and information about organizations that provide assistance related to the topic.

Photovoice and digital stories have been used to study sexual violence against girls in school; to better understand service provider and community attitudes related to HIV positive women who have experienced violence; to document alternative masculinities; to share the experiences of advocates who are spreading messages of zero tolerance; and for so many other initiatives.

Additional Resources:

Digitial stories on gender, human rights and violence against women (Sonke Gender Justice). Available in English with accompanying discussion guides.

Digital stories of youth experiences in Brazil (Promundo and Silence Speaks). Available in Portuguese with English subtitles.

Digital stories on domestic and intimate partner violence (Close to Home). Available in English.

Video for Change: online training video (WITNESS). Available in English, French and Spanish with an accompanying manual in English, French, Russian and Spanish.

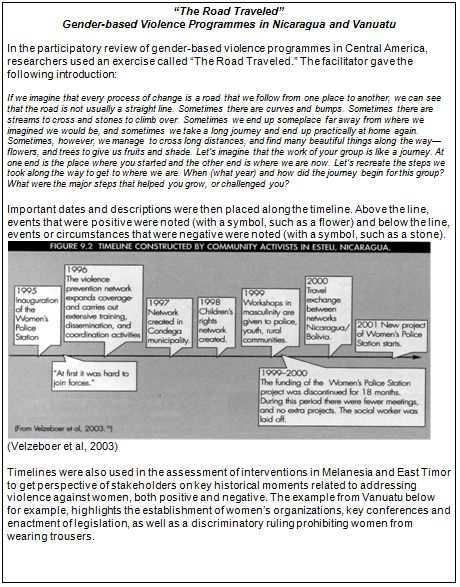

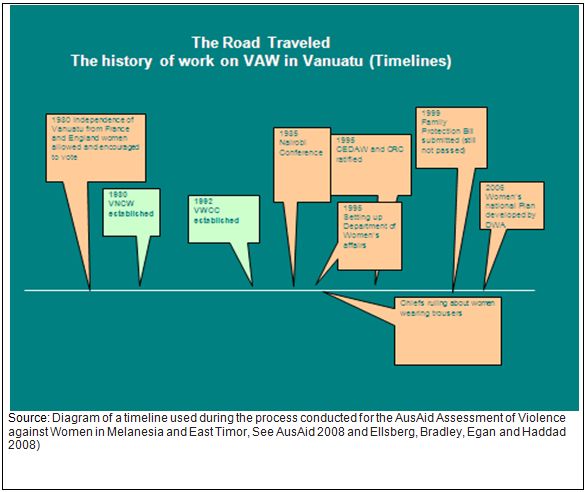

Timelines

Timelines or seasonal calendars are useful for exploring trends over time, and important events leading up to certain changes. They can be used to measure experiences at a national level (for example, the events leading up to specific changes in domestic violence legislation). They are also useful for diagramming change in a community (e.g., when social violence became a serious problem) or personal experiences in the life of an individual (for example, when a woman first started being abused by her husband, and what actions she subsequently took to overcome the violence). (Ellsberg and Heise, 2005)

In a timeline, events or trends are charted according to years, months, or days. Events may be plotted along a line, or a line may be plotted along a vertical axis to indicate increases in the frequency or severity of a specific problem. A common method in participatory research is to have community members diagram or “draw” the timeline or calendar on the ground using sticks and other natural items (such as leaves, rocks, or flowers) to mark key events. It is often helpful to involve multiple stakeholders (e.g. staff and volunteers from a women’s shelter, women activists, and members of the police who work with survivors of violence), who can collectively recollect the history and sequence of events related to the issue being explored.

Focus Group Discussions

Focus group discussions are a powerful method for collecting information relatively quickly. They are better suited for exploring norms, beliefs and practices than for seeking information on actual behaviours or details of individual lives. The focus group is a special type of group in terms of its purpose, size, composition, and procedures. A focus group is usually composed of six to ten individuals who have been selected because they share certain characteristics that are relevant to the topic to be discussed. In some cases, the participants are selected specifically so that they do not know each other, but in many cases that is not possible, particularly when participants belong to the same community or organization. The discussion is carefully planned, and is designed to obtain information on participants’ beliefs about and perceptions of a defined area of interest. (Ellsberg and Heise, 2005)

Focus groups differ in several important ways from informal discussion groups:

- Specific, predetermined criteria are used for recruiting focus group participants.

- The topics to be discussed are decided beforehand, and the moderator usually uses a predetermined list of open-ended questions that are arranged in a natural and logical sequence.

- Focus group discussions may also be carried out using participatory techniques such as ranking, story completion, or Venn diagrams. This may be particularly useful when working with groups with little formal education or when talking about very sensitive issues. (In the Nicaraguan study on a new domestic violence law, described in the following pages, however, participatory techniques were used successfully in focus group discussions with judges and mental health professionals as well as with rural men and women.)

- Unlike individual interviews, focus group discussions rely on the interactions among participants about the topics presented. Group members may influence each other by responding to ideas and comments that arise during the discussion, but there is no pressure on the moderator to have the group reach consensus.

- Focus groups have been used successfully to assess needs, develop interventions, test new ideas or programmes, improve existing programmes, and generate a range of ideas on a particular subject as background information for constructing more structured questionnaires. However, they are not easy to conduct. They require thorough planning and training of group moderators.

When planning a focus group, consider the following recommendations:

- Focus groups require trained moderators. Three types of people will be needed: recruiters, who locate and invite participants; moderators, who conduct the group discussions; and note-takers, who list topics discussed, record reactions of the group participants, and tape-record the entire discussion (if all participants give consent). Note-takers also help transcribe the taped discussions.

- Focus groups are usually composed of homogeneous members of the target population. It is often a good idea to form groups of respondents that are similar in terms of social class, age, level of knowledge, cultural/ethnic characteristics, and sex. This will help to create an environment in which participants are comfortable with each other and feel free to express their opinions. It also helps to distinguish opinions that might be attributed to these different characteristics among groups.

- If possible, experienced focus group leaders suggest conducting at least two groups for each “type” of respondent to be interviewed.

- The optimal size group consists of six to ten respondents. This helps ensure that all individuals participate and that each participant has enough time to speak. However, sometimes, it is not possible to regulate the size of a group, and successful focus group discussions have been carried out with many more participants.

- Analyze the data by group. Data analysis consists of several steps. First, write summaries for each group discussion. Next, write a summary for each “type” of group (e.g., a summary of all discussions conducted with young mothers). Finally, compare results from different “types” of groups (e.g., results from groups of young versus older mothers).

- The discussions may be taped for transcription later, but this substantially increases the time and cost of analysis. One alternative is to take careful notes during the discussion and to refer to the audiotapes for specific areas where there are doubts.

- Focus groups give information about groups of people rather than individuals.

- They do not provide any information about the frequency or the distribution of beliefs or behaviour in the population. When interpreting the data, it is important to remember that focus groups are designed to gather information that reflects what is considered normative in that culture. In other words, if wife abuse is culturally accepted, then it should not be difficult to get participants to speak frankly about it. However, some topics are very sensitive because they imply actions or orientations that are either culturally taboo or stigmatizing. For the same reason, focus group respondents should not be asked to reveal the details of their individual, personal lives in a focus group setting, especially when the subject matter of the focus group deals with sensitive issues such as domestic violence and sexual abuse. If a researcher wants information on women’s individual experiences, then that should be done in private individual interviews. In many cases, facilitators ask respondents to think about the perspectives and behaviour of their peers, for example, which allows them to draw on their experiences in general terms but does not ask them to reveal the details of their own behaviour or experiences in a group setting.

Focus Group Discussion: Advocating for a New Domestic Violence Law in Nicaragua

The Nicaraguan Network of Women against Violence used focus group discussions in the consultation process for a new domestic violence law that was presented before the National Assembly. Because the new law was controversial (it criminalized inflicting emotional injuries, and established restraining orders for abusive husbands), the purpose of the study was to assess both the political and technical viability of the new law.

The research team conducted 19 focus groups with over 150 individuals representing different sectors of the population, such as urban and rural men and women, youth, police officers, survivors of violence, judges, mental health experts, and medical examiners.

The main questions asked by the study were:

- What kinds of acts were considered violent?

- What kinds of legal measures were considered to be most effective for preventing violence?

The researchers used ranking, Venn diagrams, and free listing exercises to initiate discussions. A team of men and women from member groups of the Network were trained as focus group moderators, and two team members led each group. Focus groups sessions were audio-taped and researchers presented typed notes and diagrams from each session. The team did the analysis as a group, and participants’ responses were organized according to themes.

The study revealed a broad consensus on several issues, the most significant of which were the gravity of psychological injury and the importance of protective measures for battered women. It was widely agreed that the psychological consequences of abuse were often much more serious and long-lasting than physical injuries and that the legal definition of injury should take this into account. One rural woman noted that harsh and demeaning words can make one “feel like an old shoe.” A judge noted that “bruises and cuts will heal eventually but psychological damage lasts forever.” The results of the study were presented in testimony to the Justice Commission of the National Assembly, which subsequently ruled unanimously in favor of the law.

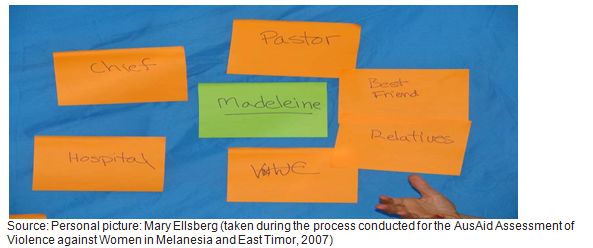

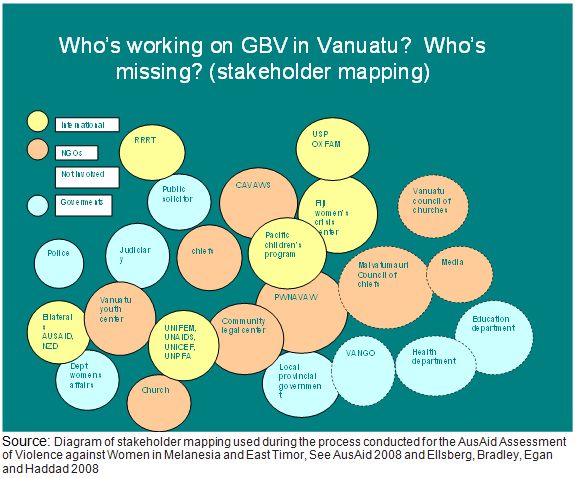

Stakeholder Mapping

Similar to community mapping and venn diagrams, stakeholder mapping is a useful participatory tool for visualizing, from the perspective of the community, the range of actors that are involved or should ideally be involved in addressing violence against women. Stakeholders might include safe houses, community-based groups that provide legal, psycho-social, economic or other forms of support for survivors of violence, support networks for women living with violence, NGOs engaged in advocacy, legal and health care services, government entities responsible for developing and implementing meaningful policies and laws and international organizations that may provide support or technical assistance.

Community maps can also highlight relationships, collaboration and coordination between organizations and sectors, as well as gaps and weaknesses in this area. Community mapping is ideal during formative assessments and as a tool for monitoring progress with respect to strengthening the role and capacity of stakeholders in addressing violence against women and empowering women to claim their rights and maneuver the often complex network of organizations involved in responding to violence against women.

Melanesia Stakeholder Mapping on Violence Prevention

The stakeholder mapping was done with groups whose members represented more than one sector (e.g. multisectoral commissions on violence prevention). The participants mapped out all the stakeholders who were involved in some way with violence prevention. Different colors were used to indicate whether the groups were governmental agencies, NGOs, civil society organizations or international agencies. The size of the circle that included the name of the group varied based on the importance of their participation (i.e. the bigger the circle, the more important the group). Then, participants were asked to name groups or individuals who were not involved in violence prevention, but should be. These stakeholders were encircled with dotted lines

Source: Ellsberg, Bradley, Egan and Haddad 2008

Additional Resources:

The C-Change: Innovative Approaches to Social and Behavior Change Communication, Available in English.

The Most Significant Change Technique: A Guide to Its Use, Rick Davies and Jess Dart. Available in English.

The International Institute of Education and Development’s website, Participatory Learning and Action section. Available in English.

The Resource Centers Participatory Learning and Action website. Available in English.

Listening to Young Voices: Facilitating Participatory Appraisals on Reproductive Health with Adolescents (Care International Zambia, 1999). Available in English.

Monitoring and Evaluation with Children (Plan Togo, 2006). Available in English.

Methods for Reflection and Knowledge Sharing from the Knowledge Sharing Toolkit (ICT-KM Program, CGIAR, Food and Agriculture Organization and UNICEF). Available in English.