What is pedagogy?

Pedagogy is the way that content is delivered, including the use of various methodologies that help different children to engage with educational content and learn more effectively, recognizing that individuals learn in different ways. Training in pedagogy can be provided to teachers through pre-service training at teacher training colleges, as well as through in-service training and other continuing professional development.

Pedagogy and teacher training are important for SRGBV, as what children learn and how it is taught are fundamental to their experiences in school. To tackle violence in and around schools, teachers need to be more aware of the various dynamics in their classrooms, including gender, power and racial or ethnic dynamics, as well as being more aware of their own biases and behaviours. One key objective of more inclusive educational settings, building on Freire’s principles (Barroso, 2002), is for teachers to make the ‘hidden curriculum’ – the attitudes, values and norms that pupils learn from the institutional structures, relationships and systems around them – more overt and visible and to teach children how to critically analyse these structures and norms. Teachers should practice equality of pedagogy, in that girls and boys receive the same respectful treatment and attention, follow the same curriculum and enjoy teaching methods and tools free of stereotypes and gender bias and that present positive images of boys and girls and other aspects of diversity (adapted from Huxley, 2009).

|

Practical action – How to teach non-violent and positive masculinity? What can teachers do to encourage men and boys to be more active in ending violence against women and girls? 1. Understand the impact of violence on their students. 2. Create a physically and emotionally safe school environment. 3. Make your view about what it means to be a man clear, including acknowledging social norms and pressures. 4. Model respect and integrity. 5. Encourage learners to support each other. 6. Involve and educate parents. 7. Bring in support from experts on non-violence. 8. Provide educational materials to pupils, parents and colleagues. 9. Teach students about healthy relationships and alternatives to violence. Source: Sonke, 2012. One Man Can: Action Toolkit |

Good methodologies are available for improving pedagogy; however, they have rarely been applied systematically. In many cases, poorly resourced teachers, and school heads in particular, see them as too costly, difficult and time-consuming to put into practice. (For examples of good methodologies, please see further resources on prevention: curriculum, teaching and learning).

In order to better understand how to deliver the curriculum most effectively, teachers must learn how to engage with gender issues and to address the inequitable treatment of girls and boys, and especially of children who do not conform to binary gender expressions and gender norms in their classrooms. This is not, therefore, just about understanding or avoiding sexist behaviour, but also about understanding gender norms and expectations and the reactions faced by LGBTI children in particular, and seeking to address social and gender discrimination – or at a minimum, not tolerate and replicate them in the classroom.

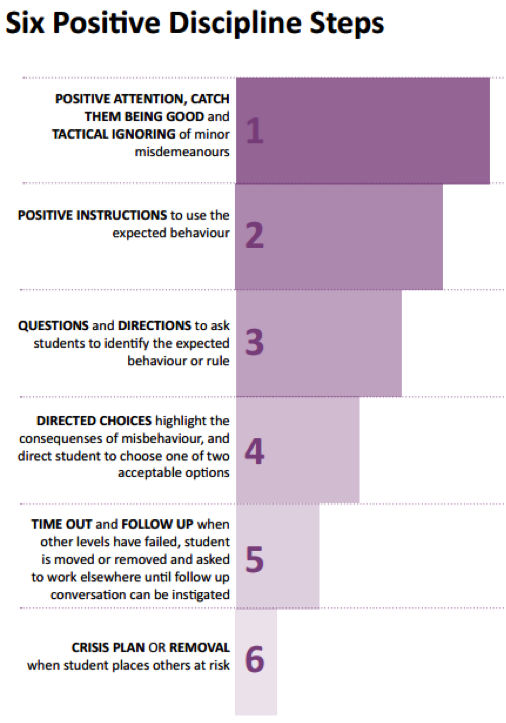

Teachers also need capacity-building support in effective classroom management techniques that promote respect and do not reinforce violence. In many classrooms, for instance, corporal punishment and discipline underpin gender-based violence. Corporal punishment is itself a widely reported form of violence in schools in many parts of the world (UNESCO/UNGEI, 2015). While corporal punishment in schools has historically been discussed and researched in gender-neutral terms, punishment and discipline are often highly gendered in practice, and are pivotal in enforcing gender roles and expected behaviour in schools. Equipping teachers with strategies and skills for maintaining discipline in a manner that is positive and affirming should thus also be rooted in gendered approaches.

Teacher training should therefore explore teachers’ own gendered lives and how these influence the way they approach their work and relationships. This kind of training can show teachers how they, as gendered beings, can create a lack of cooperation between boys and girls (the sexes), thus reinforcing sexism and creating an enabling environment for gender-based violence (Chege, 2006).

The training curriculum for teachers should therefore look at gender discrimination broadly and build awareness of SRGBV as a manifestation of this discrimination and develop capabilities to detect and prevent SRGBV. Teachers and school staff should be informed about institutional codes of conduct, as well as about how to respond appropriately to students who are experiencing, witnessing or perpetrating violence.

Pre- and in-service teacher training needs to be improved to offer teachers more tools (hard and soft skills) to manage diverse classrooms and to deal with conflict, including discrimination, racism and homophobia. Teachers must also receive support to be more interactive and less didactic in their approaches to teaching; a key opportunity for improving teachers’ skills is during pre-service training when approaches to discipline, classroom management and teaching are introduced. Many teacher training courses give subject matter training together with scripted lesson plans and tools that undermine training in more participatory and child-friendly pedagogies, so coherence in these approaches is needed.

|

Practical action – How to practise positive discipline? Positive discipline is an approach to student discipline that focuses on strengthening positive behaviour rather than just punishing negative behaviour. Teachers aim to reward positive behaviour with their attention. They work with the class to construct positive rules and expectations. Sanctions for negative behaviour are applied to help children learn, rather than to inflict suffering, humiliation or fear (Rogers, 2009).

|

Several studies have found that abusive behaviour and discriminatory attitudes are learned in teacher training establishments. For example, research in teacher training colleges has found widespread sexual harassment of female staff and students (Bakari and Leach, 2007). Therefore, reporting mechanisms will be critical as well as other measures to ensure these institutions, like any learning environment, are held to account.

Curricula at teacher training colleges should include gender transformative content in order to help teachers explore ways in which gender discrimination and norms can be challenged within schools. Teachers and school administrators’ own life histories, beliefs and experiences are a useful starting point for exploring of the way gender discrimination and SRGBV are understood. Training courses can help by revealing how teachers talk about their lived experiences as women and men, how they see their role as teachers of gender, and how they understand their relationships with their female and male colleagues and with their female and male students.

|

Country example – Doorways III Teacher Training Manual on SRGBV Prevention and Response, Ghana and Malawi As part of the Doorways training programme for the five-year USAID-funded Safe Schools Program (2003–2008) a training manual was produced to train teachers to help prevent and respond to SRGBV by reinforcing teaching practices and attitudes that promote a safe learning environment for all students. The teacher training programme was complemented with training for students and community counsellors and additional interventions such as radio, drama, gender clubs, extra-curricular activities and assemblies. Modules in the training programme included: |

|

Attitudes towards young people |

o What are my attitudes regarding my students? o Qualities of an ideal teacher |

|

Gender |

o Introduction to gender including the spectrum of gender expression o Gender, education and the classroom o Social and gender norms and stereotypes o Understanding cultural and social change |

|

Violence and SRGBV |

o Defining violence and SRGBV o Power, use of force and consent o What to do if you witness an incident of SRGBV? o Gender violence, gender norms and HIV/AIDS |

|

Human rights |

o Introduction to human rights o Convention on the Rights of the Child o Children’s rights – whose responsibility are they? |

|

Creating a safe and supportive classroom environment |

o Positive discipline o Classroom management |

|

Response – support, referral and reporting |

o What is meant by response? o Direct support to students o Using the teachers’ code of conduct to address SRGBV o Using the legal system to address SRGBV |

|

In 2009, the final evaluation using a baseline/endline survey of 400 teachers in Ghana and Malawi found that several improvements in teachers’ attitudes about gender norms and SRGBV and classroom practices were achieved over the lifetime of the programme. For example: - In Ghana, there was a nearly 50 per cent increase in teachers who thought girls could experience sexual harassment in school – from 30 per cent (baseline) to nearly 80 per cent (endline). There were similar increases when teachers were asked if boys could experience sexual harassment in school. - There was an important change in teachers’ attitudes around corporal punishment, with a 20–30 per cent increase in the percentage of teachers in both countries who said that it was not permissible to whip boys to maintain discipline in class. However, this change in attitudes had not yet filtered through to a change in teachers’ behaviours, with two-thirds of teachers in Ghana and 14 per cent in Malawi having whipped or caned a student in the last 12 months. Source: DevTech (2008); USAID (2009b) |

|

Example: Empowering Education Programme, Ukraine The Empowering Education Programme started in the Ukraine in 1996 and later expanded to 10 further countries. The programme developed a curriculum and pedagogical approach that encouraged teachers to be more interactive and helped students to become more aware of power dynamics and to learn how to challenge gender discrimination and prevent violence. The programme, while labour and time intensive, reported significant changes in students’ self-confidence and self-efficacy and reduced violence (Suslova, 2015). |

|

Example: Safe and Strong School Initiative, Indonesia The Safe and Strong Initiative was developed by UNICEF and the University of Melbourne with the aim of preventing violence in schools by helping primary and secondary school teachers to learn alternative methods of positive discipline. The initiative was piloted in three cities in the Indonesian province of Papua. Teacher training workshops were designed and delivered using a participatory approach. The initiative also included training materials in positive discipline approaches for teachers and an engaging curriculum for students focusing on social and emotional learning (Cahill and Beadle, 2013). Early findings from the pilot initiative found that positive class rules meant that fewer children broke class rules and more children displayed positive behaviour, even when there was no teacher in the classroom (UNESCO, 2014). |