Overview of the importance of monitoring and evaluation of health sector initiatives

- The evidence base around the effectiveness of different strategies and interventions in the health sector, while growing, is still weak in many areas. This poses challenges on a number of levels. Where thorough assessments are not available, decisions regarding how resources should be spent and what programmes should be supported may be made on the basis of incomplete information or findings from evaluations that are inappropriate for the specific contexts. In the worst cases, without proper evaluation programmes may also be doing more harm than good for survivors.

- Evaluations provide a framework for identifying promising interventions, targeting specific aspects of those interventions that contribute to their success, and drawbacks and gaps with each strategy. Without this information, critical resources might be wasted on programmes that will not lead to desired outcomes or may even worsen the situation for women.

- Ideally, a health programme should be able to measure progress toward its objectives and evaluate whether an intervention has been beneficial or has created additional risks. However, many health programmes carry out activities without clarifying what results they are trying to achieve or determining whether or not they did in fact achieve those results. (Guedes 2004, Bott, Guedes and Claramunt 2004)

- Health programmes that address violence have a particularly great responsibility to invest in monitoring and evaluation given the possibility that a poorly-planned intervention can put women at additional risk or inflict unintended harm. For example, a training session may fail to change misperceptions and prejudices that can harm victims of violence, or may even reinforce them. Or a routine screening policy may be implemented in ways that actually increase women’s risk of violence or emotional harm.

- Monitoring and evaluation offer invaluable information about the best way for health programmes to protect the health, rights and safety of women who experience violence.

- Health services provide a unique window of opportunity to address the needs of abused women and are essential in the prevention and response to violence against women and girls, since most women come into contact with the health system at some point in their lives. The health sector is frequently the first point of contact with any formal system for women experiencing abuse, whether they disclose or not. Every clinic visit presents an opportunity to ameliorate the effects of violence as well as help prevent future incidents. Monitoring and evaluating these service in the health sector is crucial to the broader response to violence against women and girls. (Heise, Ellsberg and Gottomoeller, 1999)

- Monitoring and evaluation should look at all elements of the system-wide approach to health, including the policies, protocols, infrastructure, supplies, staff capacity to deliver quality medical and psychosocial support, staff training and other professional development opportunities, case documentation and data systems, the functioning of referral networks, safety and danger assessments, among other items that are relevant to specific contexts and programmes. (See Heise, Ellsberg and Gottomoeller, 1999, Velzeboer et al 2003, Bott, Guedes and Claramunt 2004)

Conducting an evaluation of health sector interventions

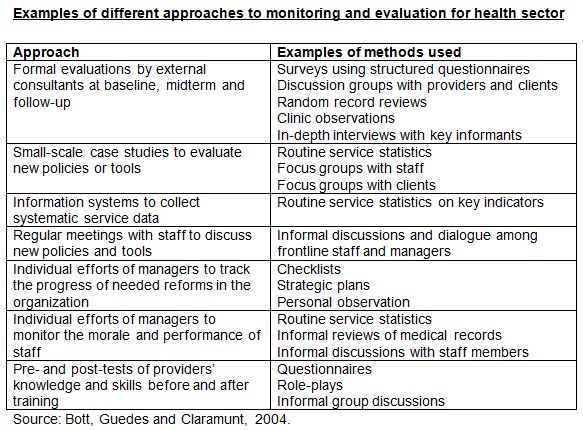

Keep in mind that evaluations should be based on operational and theoretical frameworks and that they should be incorporated in a programme’s planning stages. Baseline and situation analyses are critical to monitoring and evaluation efforts, but rarely conducted. Please refer to the introductory section for additional information on developing an appropriate framework and collecting baseline data. (Bott, Guedes and Claramunt, 2004)

- Define a clear programmatic goal for the intervention - A goal reflects the basic, very broad, conceptual aim of the project and the desired long-term outcome.

Examples of possible goals include:

1) To improve the quality of care that survivors of gender-based violence receive in health care settings.

2) To strengthen the ability of the health care sector to prevent gender-based violence.

Keeping this overall goal in mind, identify clear objectives and expected results.

- Remember to keep in mind the difference between proposed activities, outputs and outcomes, between what will be undertaken, what will be produced and what is expected will happen as a result. For example:

- Activities might include conducting training for health service providers or developing standardized protocols for responding to cases of sexual violence.

- Outputs might include the number or percentage of health service providers in a target area who have been trained or the number of health care facilities that have adopted standardized protocols for responding to cases of sexual violence.

- Outcomes might include strengthened capacity on the part of health service providers to respond to violence against women in a meaningful, appropriate manner or an integrated response on the part of the health care facility following standardized protocols.

Develop indicators for measuring each of the objectives

- Remember to distinguish between process and results indicators. Health programmes usually collect data on processes rather than on results or outcomes and may not focus on whether their activities were beneficial or effective. This does not mean however, that monitoring and evaluation frameworks should exclude process indicators.

- Process Indicators are used to monitor the number and types of activities carried out, such as the number and types of services provided, number of people trained, number of materials produced and disseminated or number and percentage of clients screened.

- Results Indicators are used to evaluate whether or not the activity achieved the intended objectives. Examples include indicators of providers’ or community level knowledge, attitudes and practices as measured by a survey, women’s perceptions about the quality and benefits of services provided by an organization or institution as measured by individual interviews, women’s experiences with health care, and the appropriateness or readiness of health unit capacity and infrastructure. (Bott, Guedes and Claramunt, 2004)

Examples of strategies, objectives and indicators for monitoring and evaluation of health sector initiatives

|

Strategy/ intervention |

Examples of possible objectives |

Example indicators |

|

1) Dissemination of materials/ information |

Raising health care providers’ awareness and understanding of gender-based violence, in particular: a) GBV as a critical human rights and public health issue b) barriers women living with violence or survivors of violence face when accessing services c) links between GBV and HIV and AIDS d) laws addressing GBV and providers’ responsibilities |

|

|

2) Training of service providers |

Strengthening health care providers’ ability to respond to cases of gender-based violence [in particular…] a) following appropriate routine screening protocols b) responding to cases of rape and sexual violence c) addressing GBV and HIV/AIDS links holistically d) establishing and using community-based referral networks of care providers and social services e) improving medico-legal documentation of cases f) changing stigmatizing norms and attitudes g) providing emergency and crisis care

Strengthening health care providers’ ability to prevent possible gender-based violence through: a) changing stigmatizing norms and attitudes b) strengthening capacity to screen for possible violence, provide appropriate care and referrals as necessary |

|

|

3) Development of protocols and norms for managing GBV cases |

|

|

|

4) Routine screening |

|

|

|

5) Campaigns to empower women |

|

|

Source: PATH, 2010.

Case Study: International Planned Parenthood Western Hemisphere Region Evaluation to Improve the Health Sector Response to Gender-Based Violence

The evaluation included four main components.

1. A baseline evaluation study including:

A knowledge, attitudes and practices survey of providers using face to face interviews. IPPF/WHR designed a survey questionnaire to gather information on health care providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to gender-based violence. The questionnaire contains approximately 80 questions. Although the questionnaire includes a few open-ended questions, most of the questions are closed-ended so that the results can be tabulated and analyzed more easily. The questionnaire covers a range of topics, including: whether, how often and when providers have discussed violence with clients; what providers think are the barriers to screening; what providers do when they discover that a client has experienced violence; attitudes toward women who experience violence; knowledge about the consequences of gender-based violence; and what types of training providers have received in the past. This questionnaire can also be adapted to evaluate a single training. One possibility is to use all or part of the questionnaire before the workshop begins and use only part of the questionnaire after the workshop is over. If the questionnaire is used immediately “before and after” a single training, the organization may be able to measure changes in knowledge, but changes in attitudes and practices usually take time.

A clinic observation/ interview guide The Clinic Observation/Interview Guide gathers information on the human, physical, and written resources available in a clinic. The first half of the guide consists of an interview with a small group of staff members (for example, the clinic director, a doctor, and a counselor). This section includes questions about the clinic’s human resources; written protocols related to gender-based violence screening, care, and referral systems; and other resources, such as whether or not the clinic offers emergency contraception. Whenever possible, the guide instructs the interviewer to ask to see a copy or example of the item in order to confirm that the material exists and is available at the clinic. The second part of this guide involves an observation of the physical infrastructure and operations of the clinic, including privacy in consultation areas (for example, whether clients can be seen or heard from outside), as well as the availability of informational materials on issues related to gender-based violence.

2. Service statistics on detection rates and services provided using standardized screening questions and indicators.

Sample tables for gathering screening data. To ensure that all three participating associations could collect comparable screening data, IPPF/WHR developed a series of model tables, which each association completed every six months. These tables may or may not be useful for other health programmes, as this depends on whether or not the health programme decides to implement routine screening, what kind of policy it adopts, what kind of questions it asks, and what kind of information system it has. Nevertheless, these tables illustrate the types of data that can be collected and analyzed on a routine basis.

3. A midterm, primarily qualitative, evaluation including:

Focus group discussions and in-depth interviews with providers, survivors and external stakeholders/key informants: A summary protocol for collecting qualitative data describes these methods, including in-depth interviews and group discussions; and also provides an idea of what types of providers, clients and other stakeholders were asked to participate.

Client satisfaction surveys: The Client Exit Survey Questionnaire is a standard survey instrument for gathering information about clients’ opinions of the services they have received. This survey is primarily designed for health services that have implemented a routine screening policy. It is important to note that exit surveys tend to have a significant limitation: many clients do not want to share negative views of the services, especially when the interview is conducted at the health center. IPPF/WHR was not able to interview clients offsite, but it did arrange for all the interviewers to be from outside the organization, so that they could reassure the women who participated that they were not going to breach their confidentiality. This questionnaire contains mostly closed-ended questions about the services. It asks women whether they were asked about gender-based violence and about how they felt answering those questions; however, the questionnaire does not ask women to disclose whether or not they have experienced violence themselves.

Case studies of pilot strategies to address various aspects of gender-based violence.

4. A final evaluation serving as a follow up to the baseline including:

KAP survey of providers using face to face interviews

A clinic observation/ interview guide

Random records reviews and development of a protocol:

Throughout the course of the IPPF/WHR regional initiative, the participating associations gathered routine service statistics about clients, including the numbers and percentages of clients who said yes to screening questions. However, the quality of these service statistics depends on the reliability of the information systems and the willingness of health care providers to comply with clinic policies—both of which may vary from clinic to clinic. IPPF/WHR therefore designed a protocol to measure screening levels and documentation using a random record review approach. This manual contains a brief description of the protocol as well as a tabulation sheet.

Download the main publications related to this initiative:

Basta! The Health Sector Addresses Gender-Based Violence. Available in English and Spanish.

Improving the Health Sector Response to Gender-Based Violence. . Available in English and Spanish.

Source: Bott, Guedes and Claramunt 2004)

Indicators

MEASURE Evaluation, at the request of The United States Agency for International Development and in collaboration with the Inter-agency Gender Working Group, compiled a set of indicators for the health sector. The indicators have been designed to measure programme performance and achievement at the community, regional and national levels using quantitative methods. Note, that while many of the indicators have been used in the field, they have not necessarily been tested in multiple settings. To review the indicators comprehensively, including their definitions; the tool that should be used and instructions on how to go about it, see the publication Violence Against Women and Girls: A Compendium of Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators.

The compiled indicators for the health sector are:

- Proportion of health units that have documented & adopted a protocol for the clinical management of women/girls (VAW/G) survivors of violence

What It Measures: This indicator to measures whether or not a health unit has a standard protocol to guide the identification, service provision and referral mechanism for VAW/G survivors. The protocol should describe the elements of care that should be provided, and the way in which it should take place. The protocol should be displayed or be otherwise accessible to health facility staff.

- Proportion of health units that have done a readiness assessment for the delivery of VAW/G services

What It Measures: This measures a health unit’s efforts to provide a basic level of service that can be expected to be delivered to VAW/G survivors. If there is a low proportion of facilities who have done such an assessment, it would indicate that the services being provided may be of variable quality. Once a readiness assessment is completed, health units will be in a position to look at their strengths and rectify the gaps in VAW/G service provision.

- Proportion of health units that have commodities for the clinical management of VAW/G

What It Measures: This is a measure of readiness for health units to provide VAW/G services. If the necessary commodities are not present in the health unit, presumably, VAW/G services cannot be provided at an acceptable level. The indicator does not measure the service quality with which these commodities are delivered.

- Proportion of health units with at least one service provider trained to care for and refer VAW/G survivors

What It Measures: This is an indicator of readiness for health units to provide VAW/G services. If staff have undergone no specific training, the provision of such services could be done in an inappropriate or detrimental manner. This indicator reflects training, but not the quality of the training, or how well the staff member integrated what they learned into practice.

- Number of service providers trained to identify, refer, and care for VAW/G survivors

What It Measures: This indicator is an output measure for a program designed to provide training to health service providers in VAW/G service provision. This will provide a measure of coverage of trained personnel per geographic area of interest, and will help monitor whether or not a program is attaining its target number of providers trained.

- Number of health providers trained in FGC/M management and counseling

What It Measures: This indicator is an output measure for a program designed to provide training to health service providers in the management of complications, both physical and psychosocial, resulting from FGC/M procedures. This will provide a measure of coverage of trained personnel per geographic area of interest, and will help monitor whether or not a program is attaining its target number of providers trained.

- Proportion of women who were asked about physical and sexual violence during a visit to a health unit

What It Measures: The number of women presenting for any type of care at health units who are asked about experiencing any physical or sexual violence that may have occurred, ever. The count can be determined per health unit, or per area of interest.

- Proportion of women who reported physical and/or sexual violence

What It Measures: This output indicator provides a measure of service utilization by VAW/G survivors who disclose their experience to health providers.

- Proportion of VAW/G survivors who received appropriate care

What It Measures: This output indicator provides a measure of adequate service delivery to VAW/G survivors who disclose their experience to health providers. This does not assess the quality of service delivery.

- Proportion of rape survivors who received comprehensive care

What It Measures: This output indicator provides a measure of adequate service delivery to rape survivors who present at health units. This does not assess the quality of service delivered.

Baseline (and endline) assessment methods

Four general areas for baseline data include:

- Assessing providers knowledge, attitudes and practices

- Assessing appropriateness and readiness of health unit infrastructure and capacity

- Assessing women’s experiences with health care

- Assessing compliance with policies and protocols

Assessing providers’ level of knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) related to violence against women and girls

Information on providers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices can help managers understand what their staff knows and believes about violence, what issues need to be addressed during training, and what resources are lacking in the clinics or health centers. Moreover, this information can be used to document a baseline so that health programmes can measure changes in providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices over time.

A couple of ways to collect information on providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices, include surveys and gathering qualitative data through group discussions or other participatory methods with providers. Qualitative data can provide an in-depth understanding of providers’ perspectives. Quantitative data makes it easier to measure change over time.

Knowledge attitude and practices surveys of health care providers are useful because they:

- offer information about whether, how often and when providers have discussed violence with clients; what providers think are the barriers to screening; what providers do when they discover that a client has experienced violence; providers’ discriminatory or stigmatizing attitudes; attitudes toward women who experience violence; knowledge about the consequences of gender-based violence; and what types of training providers have received in the past; and

- can be used as a convenient pre and post intervention measure.

It is best to use or adapt already designed and validated instruments and questions.

Resources:

World Health Organization Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women (WHO). The survey includes questions to gauge attitudes towards violence against women. Available in English.

Gender-Equitable Men (GEM) Scale (Horizons and Promundo). The scale measures attitudes toward “gender-equitable” norms, provide information about prevailing norms in a community and the effectiveness of programmes hoping to influence them. Available in English, Spanish and Portuguese. The scale used in Ethiopia is also available in English.

National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey 2009 (The Victorian Health Promotion Foundation) has subsections focusing on attitudes towards domestic violence and sexual violence using a scale of agreement or disagreement. Available in English.

The Attitudes Towards Rape Victims Scale (The Arizona Rape Prevention and Education Project). These scales are self administered instruments designed to assess individuals’ attitudes towards rape victims rather than towards rape in general. Available in English

The Sexual Violence Research Initiative compiled a comprehensive package of programme evaluation tools and methods for assessing service delivery, knowledge, attitudes, practices and behaviours in sexual violence projects and services. By making such materials available to service providers, managers, researchers, policy makers and activists, among others, the hope was that evaluation could be more easily incorporated into project and programme plans. The assessment instruments are drawn from articles in peer-reviewed journals that report findings from evaluations of health care-based services and interventions for women victims/survivors of sexual violence, written in English or Spanish, published between January 1990 and June 2005. The instruments are available from the evaluation section of sexual violence research initiative website.

Semi-structured interviews with health care providers are useful because they:

- offer insight into providers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices; and

- offer the potential for digging deeper into any challenges, barriers, concerns that may affect ability to provide care.

International Planned Parenthood Federation, Western Hemisphere Region’s (IPPF/WHR’s) Survey of Provider Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAP): This face-to-face interview is designed for administration to women’s health care providers. It focuses on providers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices concerning violence in the lives of their patients. There are approximately 80 questions (most close-ended), that cover a range of topics, including: whether, how often and when providers have discussed violence with clients; what providers perceive of as barriers to screening; what providers do when they identify a client who has experienced violence; attitudes toward women who experience violence; knowledge about the consequences of gender-based violence; and the types of training providers have received in the past. Available in English and Spanish.

Forensic and Medical Care Following Sexual Assault Service Education Programme Evaluation Questionnaire: This questionnaire is designed to assess medical personnel’s knowledge and satisfaction concerning their abilities to treat sexual assault patients, and includes questions such as “How would you rate your ability in forensic evidence collection?”. It can be self-administered or used as an interview guide.

Qualitative, participatory methods with clinic/ health unit staff including focus group discussions, open-ended stories, mapping, role plays, Venn diagrams and others can be useful, because they:

- offer insight into provider’s knowledge, attitudes and practices; and

- offer insight into institutional practices and norms, as well as group dynamics and work flow.

See the section on qualitative methods for ideas and examples of what can be used.

Assessing appropriateness of clinic/ health unit infrastructure and capacity

Improving the health sector response to gender-based violence has implications for many aspects of the way a clinic functions. For example, ensuring adequate care for women who experience violence may require private consultation spaces, written policies and protocols for handling cases of violence, client flow that facilitates meaningful care, access to emergency contraception, and a directory of resources in the community. One way to assess what resources exist in a clinic is to have an independent observer visit the clinic and assess the situation through firsthand observation. Another way to do this is for a group of staff to complete a checklist or self administered questionnaire that includes resources that are important for providing quality care to survivors of violence.

Methods that can be used include:

- Clinic observations

- Confidential interviews with clinic staff are an excellent source of information about the infrastructure, protocols and capacity of the health care facility. However, they require time and confidentiality assurances, and staff may not want to get involved in critical evaluations of the facility that employs them.

- Questionnaires/ management checklist are an easy, resource friendly monitoring mechanism. A management checklist can be used for monitoring what measures an institution has taken to ensure an adequate response for women experiencing gender-based violence.

- Review of protocols and policies

Example Monitoring Checklist of Minimum Key Elements of Quality Health Care for Women Victims/Survivors of Gender-Based Violence

All health organizations have an ethical obligation to assess the quality of care that they provide to all women, whether through full evaluations and/or ongoing, routine monitoring activities. An assessment could also look at the minimum elements required to protect women’s safety and provide quality care in light of widespread gender-based violence, as listed below:

1. Institutional values and commitment: Has the institution made a commitment to addressing violence against women, incorporating a “system’s approach”? Are senior managers aware of gender-based violence against women as a public health problem and a human rights violation, and have they voiced their support for efforts to improve the health service response to violence?

2. Alliances and referral networks: Has the institution developed a referral network of services in the community, including to women’s groups and other supports? Is this information accessible to all health care providers?

3. Privacy and confidentiality: Does the institution have a separate, private, safe space for women to meet with health care providers? Are there protocols for safeguarding women’s privacy, confidentiality and safety, including confidentiality of records? Do providers and all who come into contact with the women or have access to records understand the protocols?

4. Understanding of and compliance with local and national legislation: Are all providers familiar with local and national laws about gender-based violence, including what constitutes a crime, how to preserve forensic evidence, what rights women have with regard to bringing charges against a perpetrator and protecting themselves from future violence, and what steps women need to take in order to separate from a violent spouse? Do health care providers understand their obligations under the law, including legal reporting requirements (for example, in cases of sexual abuse) as well as regulations governing who has access to medical records (for example, whether parents have the right to access the medical records of adolescents)? Does the institution facilitate and support full compliance with obligations?

5. Ongoing provider sensitization and training: Does the institution provide or collaborate with organizations to provide ongoing training for staff around gender-based violence, harmful norms and practices, legal obligations and proper medical management of cases?

6. Protocols for caring for cases of gender-based violence: Does the institution have clear, readily available protocols for screening, care and referral of cases of gender-based violence? Were these protocols developed in a participatory manner, incorporating feedback from staff at all levels as well as clients? Are all staff aware of and able to implement the protocols?

7. Post-exposure prophylaxis, Emergency contraception and other supplies: Does the institution have supplies readily available, and arestaff properly trained on their dissemination and use?

8. Informational and educational materials: Is information about violence against women visible and available, including on women’s rights and local services women can turn to for help?

9. Medical records and information systems: Are systems in place for documenting information about violence against women as well as collating standardized data and service statistics on the number of victims of violence? Are records kept in a safe, secure manner?

10. Monitoring and evaluation: Does the institution integrate mechanisms for ongoing monitoring and evaluation of their work, including receiving feedback from all staff as well as from women seeking services? Are there regular opportunities for providers and managers to exchange feedback? Is there a mechanism for clients to provide feedback regarding care?

Source: adapted from Bott, Guedes and Claramunt 2004

Illustrative tools:

How to Conduct a Situation Analysis of Health Services for Survivors of Sexual Assault (South African Gender-based Violence and Health Initiative and Medical Research Council of South Africa). This guide provides tools and outlines steps for conducting a situation analysis of the quality of health services for victims/survivors of sexual assault. It includes a facilities checklist for collecting information on the infrastructure of the facilities where survivors are managed and where medico-legal/forensic examinations take place, including medication, equipment and tests available at the facility. It also includes a standardized health care provider questionnaire designed to be used in face to face interviews with health care providers who manage the care of survivors. Note that, the tool does not address stigma and discrimination, the time a patient waits to be seen by a provider, or what happens after the provider has completed the examination. Available in English.

Clinic Interview and Observation Guide (International Planned Parenthood Federation/Western Hemisphere Region). This assessment tool gathers information on the human, physical, and written resources available in a clinic. The first half of the guide consists of an interview with a small group of staff members (for example, the clinic director, a doctor, and a counselor). This section includes mostly closed-ended questions about services, including: the clinic’s human resources; written protocols related to gender-based violence screening, care, and referral systems; and other resources, such as whether or not the clinic offers emergency contraception. The second part of the guide involves an observation of the physical infrastructure and operations of the clinic, such as privacy in consultation areas, as well as the availability of informational materials on sexual violence. Available in English and Spanish.

STI/HIV Self-Assessment Module (International Planned Parenthood Federation/Western Hemisphere Region). This self-assessment module contains a questionnaire designed to assess whether an organization has the necessary capacity, including management systems, to ensure high quality sexual and reproductive health services. The questionnaire allows staff from different levels of an organization to assess the extent to which their organization has addressed a multitude of issues relevant to gender-based violence, including sexual violence. Available in English and Spanish.

Management of Rape Victims Questionnaire (Azikiwe, Wright, Cheng & D’Angelo). This self-administered questionnaire was designed for programme directors of pediatric and adult hospital emergency departments to report on their department’s management of care for rape survivors. The 22 questions gather information concerning the department’s volume of rape cases, screening for STDs, emergency contraception policies, medications offered or prescribed for emergency contraception, non-occupational HIV postexposure prophylaxis policies, medications offered or prescribed for HIV postexposure prophylaxis, and patient follow-up. Available for purchase in English from Elsevier.

Standardized Interview Questionnaires and Facilities Checklist (Christofides, Jewkes, Webster, Penn-Kekana, Abrahams & Martin ). This face-to-face interview questionnaire was designed to gather information from health care providers who care for rape survivors. The questionnaire contains 5 sections that collect information on: the demographic characteristics of providers; the types of services available for rape survivors; whether care protocols for rape survivors are available at the facility; whether the practitioner had undergone training in how to care for rape survivors; and practitioner's attitudes towards rape and women who have been raped. Responses to particular items are used to develop a scale that measures the quality of clinical care. In addition, the assessment tool includes a checklist that the fieldworkers complete at each health care center noting the presence or absence of equipment and medicines and the structural quality of the facilities. Available in English.

Quality of Care Composite Score (Christofides, Jewkes, Webster, Penn-Kekana, Abrahams & Martin). The Quality of Care Composite Score is a self-reported measure used at the individual practitioner level to assess the clinical care provided by doctors and nurses who care for rape victims in terms of indicators of preventive strategies for sexually transmitted infections and prevention of pregnancy, counseling, and the quality of forensic examinations. It consists of 11 items such as treatment of sexually transmitted infections and clothing or underpants ever sent for forensic testing. Available in English.

Assessing women’s experiences with health care

Strengthening the response of the health sector to gender-based violence requires an understanding of women’s experiences accessing or attempting to access health services. This includes measures taken to understand and address the barriers and challenges women experiencing violence face when seeking care. This is most feasible through interviews with women as they are leaving the health care institution. It may be difficult for women to feel comfortable saying something critical about the services they have received while they are on the premises. If possible, additional interviews and focus group discussions with women identified through other social services outside of the health care setting might be used to assess access to health service and quality of care.

Methods that can be used include:

- Qualitative, participatory methods with women accessing or attempting to access health services including focus group discussions, role plays, open-ended stories, mapping, Venn diagrams [link to descriptions of these methods]

- Client exit interviews; and

- Interviews with women unable to access health services to determine the barriers these women face and to provide a non-health care setting for women to speak more freely about their experience

Illustrative Tools:

In Her Shoes methodology (Washington Coalition on Domestic Violence). This methodology was developed by and adapted for Latin America to train and sensitize service providers on the barriers women living with violence face. It has also been adapted for Latin America in Spanish by the InterCambios Alliance.

Client Exit Survey Questionnaire (International Planned Parenthood Federation/ Western Hemisphere Region). This is a standard survey instrument for gathering information about clients’ opinions of the services they have received and is primarily designed for health services that have implemented a routine screening policy. This questionnaire contains mostly closed-ended questions about the services. It asks women whether they were asked about gender-based violence and about how they felt answering those questions; it does not ask women to disclose whether or not they have experienced violence. Available in English and Spanish.

Using Mystery Clients: A Guide to Using Mystery Clients for Evaluation Input (Pathfinder, 2006). Available in English.

Assessing compliance with policies and protocols

Routine service statistics about clients, including the numbers and percentages of clients who said yes to screening questions, are an important way to gauge an institution’s response to gender-based violence.

However, the quality of these service statistics depends on the reliability of the information systems and the willingness of health care providers to comply with clinic policies—both of which may vary from clinic to clinic. The availability and quality of statistics also depend on whether or not the health programme decides to implement routine screening, what kind of policy it adopts, what kind of questions it asks, what kind of information system it has, and the capacity of staff to collect data.

Random record reviews are a way to evaluate the completeness of record keeping with regard to screening for gender-based violence and how well providers understand and use screening policies and protocols.

Methods that can be used include:

- Review of screening data

- Review of routine service statistics

- Review of protocols and procedures by:

-Asking for documentation of all available protocols and procedures, including screening protocols

-Determining whether there are protocols and procedures for the management of gender-based violence, including sexual violence

-Determining whether the protocols are clear, unambiguous and easily accessible to all staff.

Illustrative tools:

Sample tables for gathering screening data (International Planned Parenthood Federation/ Western Hemisphere Region). This series of model tables were developed to collect comparable screening data across facilities. These tables illustrate the types of data that can be collected and analyzed on a routine basis. Their use of these tables depends on whether or not the health programme decides to implement routine screening, what kind of policy it adopts, what kind of questions it asks, and what kind of information system it has. Available in English and Spanish.

Random record review protocol (International Planned Parenthood Federation/ Western Hemisphere Region). The quality of routine service statistics such as the numbers and percentages of clients who said yes to screening questions depends on the reliability of the information systems and the willingness of health care providers to comply with clinic policies—both of which may vary from clinic to clinic. Available in English and Spanish.

Steps after Evaluation

These recommendations are extracted from International Planned Parenthood’s publication, Improving the Health Sector Response to Gender-based Violence.

- Use the findings from the baseline study during sensitization and training of staff. Findings from the provider survey can be used to identify which specific topics need to be addressed during provider sensitizations and trainings. For example, the provider survey can point to the types of knowledge and attitudes that could be discussed at a sensitization workshop.

- Hold a participatory workshop to share the results, identify areas that need work, and develop an action plan. After collecting baseline data, health programmes may find it valuable to hold a workshop with a broad group of staff members to discuss the results

- Plan to collect follow-up data using the same instruments to determine how much progress your organization has made over time. Once an organization has baseline data on providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices, as well as clinic resources, then it can repeat the survey or clinic observation at a later point and thereby measure change over time.

Illustrative health sector monitoring and evaluation reports:

Evaluating an Intervention of Post Rape Care Services in Public Health Settings (Kilonzo, Liverpool VCT, 2007). Power Point available in English.

Additional Tools and Resources:

Ver y Atender, Guía práctica para conocer cómo funcionan los servicios de salud para mujeres víctimas y sobrevivientes de violencia sexual [Getting It Right! A Practical Guide to Evaluating and Improving Health Services for Women Victims and Survivors of Sexual Violence] (Troncoso, Billings, Ortiz, Suárez/Ipas 2006). Available in English and Spanish.

Improving the Health Sector Response to Gender-Based Violence (Bott, Guedes, Claramunt,Guezmes, International Planned Parenthood Federation/ Western Hemisphere, 2004). . Available in English and Spanish.

Preventing Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Against Women: Taking Action and Generating Evidence (World Health Organization/London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2010). Available in English.

Sexual Violence Research Initiative Website, Evaluation Section. Available in English.

Positive Women Monitoring Change: A Monitoring Tool on Access to Care, Treatment and Support, Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights and Violence against Women Created by and for HIV Positive Women (International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS, 2008). Available in English.