Brief overview of Monitoring and Evaluating Justice/Legal Sector Initiatives

- It is clear that hard-earned gains in providing justice can be fragile, and that vigilant monitoring is needed to make a real difference in women’s lives, especially since effective justice systems are important in reducing and preventing violence against women, ensuring their safety, ending impunity and punishing perpetrators.

- It is critical to keep in mind two key questions when monitoring and evaluating justice/ legal sector interventions: “Are offenders held accountable?” and “Are women safer?” The answers to those two questions may differ, even when the results of an evaluation demonstrate from a criminal justice perspective that an initiative is accomplishing what it is supposed to do – such as increased rates of reporting.

- Monitoring and evaluation, when implemented consistently and purposefully, provide important information on how effective the sector is in meeting the needs of victims. A properly functioning and responsive system facilitates justice for victims and with that justice, healing, and at the same time prevents further violence. One that is not responsive can further traumatize, victimize and endanger women.

- Monitoring and evaluation should consider and assess the elements that constitute effective delivery of justice, for example, including whether women and girls know their rights under the law, and whether men are aware of them as well (and their penalties); and whether lawyers, judges, police, health providers, community leaders and others responsible for their realization and enforcement are aware of their legal obligations and are aware that violence against women is a human rights violation under the law.

- When developing a monitoring or evaluation framework, first define a clear programmatic goal for the intervention, for example:

To hold governments accountable for their obligations to protect women from violence and punish perpetrators

To strengthen the legal sector’s response to survivors of violence and capacity to prevent further violence

The timeframe and scope for monitoring and evaluation of justice/legal sector initiatives will depend on the goals and objectives of the programme and nature of strategies and activities. Ultimately, governments at the national level are responsible for ensuring that they meet their obligations to “prevent, protect and punish” violence against women and girls. This includes setting up data collection systems to routinely monitor progress towards this end.

Keeping this overall goal in mind, clear objectives, data collection needs and available sources must be identified vis-à-vis the expected results.

About data sources, issues and challenges:

- Monitoring and evaluation at the district level and community level involves the collection and collation of service statistics from police stations and courts with respect to reports of violence by women, response of the police and the trajectory of cases (how many cases are resolved with the women returning home, how many are brought to trial/prosecuted, and how many end in successful convictions or remedies, for example.)

- The criminal justice sector has the potential to collect information on both victims and perpetrators and to track repeat victimization and repeat offending.

- In most countries, however, statistics are not broken down according to the sex of the victim and do not describe the relationship of the victim to the perpetrator. It is therefore difficult to gain a complete picture of the magnitude of violence against women. Countries also differ in their treatment of violence against women under law -some with specific laws on domestic violence, others incorporating it under laws on assault, grievous bodily harm, stalking, homicide or other crimes. Different ministries (justice, health, etc.) in the same country may also record the same crime differently, based on the scope of their responsibilities.

- While they represent a very small percentage of the actual cases of violence (i.e. the total number of women that have experienced abuse), court and police statistics are important for understanding the response of the criminal justice system.

- Note that such statistics are often not collected, especially in resource poor areas, and adequate systems are not in place for documenting and following up on cases. In these cases, many researchers, women’s groups and entities interested in looking at the response to violence against women have had to first manage the bureaucratic and other barriers that may be involved with gaining access to any records (which also involves ethical concerns around privacy and confidentiality), sift through records with missing or incomplete information, and conduct their own analysis.

- In addition to reporting statistics, qualitative data on women’s perceptions of the responsiveness of the legal/justice sector, and its ability to provide meaningful, appropriate care, as well as police and court officials’ comfort level with handling cases of violence against women and sensitivity to the challenges facing survivors and victims, is another critical component to evaluating efforts in this sector.

Monitoring and evaluating justice/legal sector initiatives at the national level

At the national level, monitoring and evaluation efforts assess the degree of compliance by governments and other key actors in exercising due diligence to prevent, protect and punish acts of violence against women and girls.

Monitoring at this level should focus on assessing whether the following key elements are in place and functioning:

1. Are various forms of violence against women and girls addressed?

Violence against women and girls occurs in both private and public spaces. It takes many forms, ranging from domestic abuse to rape, psychological torture, trafficking, sexual exploitation and harmful practices, among others. Acts of violence take place in a variety of settings (households, streets, schools, workplaces, conflict situations) and affect a cross-section of groups (including rural/urban, rich/poor, young/adult, migrant, displaced, indigenous, disabled and HIV-positive women). Ensuring effective responses requires that laws, policies, services and data collection efforts recognize and address the different manifestations of violence and tailor strategies accordingly, based on an understanding of the specific contexts in which they occur.

2. Are data collection, analysis and dissemination systems in place?

Developing workable policies, programmes and responses depends on reliable data. This includes information on the prevalence, causes, survivors and perpetrators of violence against women and girls; the impact of interventions and the performance of the public sector in terms of, for instance, health service access, police and judiciary responses; the attitudes, behaviours and experiences of men, women and young people from different population groups, and how they perceive the issue in their society; and the social and economic costs of violence against women and girls. Such data are essential for measuring the progress of anti-violence initiatives, developing effective strategies and allocating budgets.

3. Do policies and programmes reflect a holistic, multisectoral approach?

Addressing violence against women and girls requires a multi-dimensional response involving government agencies, non-governmental organizations and other entities from various sectors and disciplines. Beyond the institutions that have primarily been involved in these efforts (e.g., health, public security, legal, ministries of women’s affairs), other key actors—such as educational institutions, employers, labour unions, the media, ministries of finance, and the private sector as part of corporate social responsibility—should be included. Interventions need to be composed of both services and referral systems for the survivors/victims of violence, as well as broader prevention efforts focused on social and community mobilization for ‘zero tolerance’ and gender equality. Holistic support means addressing the full range of needs and rights of women and girls, which includes ensuring safety, health services, legal and judicial remedies, and economic security for themselves, their children and other dependents.

4. Are emergency ‘Frontline Services’ available and accessible?

Survivors of gender-based violence require immediate ‘frontline’ support from the police and health and legal aid providers. As larger-scale and longer-term responses are developed, all countries should ensure that minimum standards to meet emergency needs are satisfied. Subject to national context, these should include: ensuring the safety and adequate protection of survivors/victims; universal access to at least one free national 24-hour hotline to report abuse and life-threatening situations that is staffed by trained counsellors who can refer callers to other services; one shelter for every 10,000 inhabitants that provides safe emergency accommodation, qualified counselling and other assistance; one women’s advocacy and counselling centre for every 50,000 women that offers crisis intervention for survivors/victims; one rape crisis centre for every 200,000 women; and universal access to quality post-rape care (including pregnancy testing, emergency contraception, post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV and treatment for sexually transmitted infections, treatment for injuries and psychosocial counselling). These services should not be conditional upon the survivor/victim’s reporting violence to the police, and they should be followed by longer-term health, legal, psychosocial, educational and economic support.

5. Is national legislation adequate and aligned with human rights standards?

Laws and their enforcement are essential to ending impunity. They set the boundaries for public norms and behaviours. They affirm the rights that all people are entitled to enjoy and delineate the duties and obligations of those charged with their protection. Laws to stop violence should be comprehensive and work to prevent, respond to and punish all forms of violence against women and girls. The human rights of women and girls must be placed as the paramount concern of all laws, policies and programmes—including their rights to personal security, privacy and confidentiality, informed and autonomous decision-making, to health and social services, and to justice. This also entails legal provisions safeguarding certain rights that might determine whether a woman is enabled to leave an abusive situation, namely, women’s rights to child support and custody; economic, property, land and inheritance rights; and nationality and immigration status. Whether formal or customary systems of justice prevail, they should uphold the human rights of women and girls. Laws and their enforcement should comply with international and regional human rights standards, as set forth in various conventions, agreements and mechanisms.

6. Do decrees, regulations and protocols establish responsibilities and standards?

Explicit standards should be established for the implementation and monitoring of laws, policies and programmes through various instruments and procedures that reinforce and institutionalize them. Presidential or ministerial decrees, for example, can bolster implementation by assigning specific roles and responsibilities to the relevant ministries. Protocols, both within and across sectors, can provide critical guidance to officials and service providers and set operating and performance standards. These standards can also serve as benchmarks for tracking progress and accountability and for introducing improvements. Protocols and procedures should be aligned with available internationally adopted and recommended human rights and ethical and service delivery standards.

7. Is there a National Action Plan and are key policies in place and under way?

National Action Plans devoted to addressing violence against women and girls can be valuable instruments for setting in place the institutional, technical and financial resources required for coordinated, multisectoral responses. They can establish mechanisms for accountability and can clarify institutional responsibilities. They can also serve to help monitor progress towards specific targets. Ministries charged with coordination (often women’s machineries) need political support at the highest levels of government, as well as adequate institutional and financial support to carry out this complex task effectively. Ensuring that actions to address violence against women and girls are integrated into other leading policy and funding frameworks can also provide strategic venues in which to strengthen efforts and secure budgets. Examples of these include poverty reduction and development strategies and national plans and sector-wide reforms related to education, health, security, justice, HIV and AIDS, and peacebuilding and reconstruction in post-conflict situations.

8. Are sufficient resources regularly provided to enforce laws and implement programmes?

Policies and laws are too often adopted without adequate funding being provided for their implementation. Budgets should be assessed to make sure that they meet the needs of the population, adequately serve impoverished geographic areas and ensure equity, and benefit the women and girls they are intended to serve. Financial considerations should be based on costing and should include seemingly peripheral but crucial considerations, such as free medical and legal aid and transportation support so that women and girls can access legal and other services, as well as support for their socio-economic reintegration. Financial assistance to survivors/victims can be made available through innovative schemes, such as trust funds to which both the State and other actors (individuals, organizations and private donors) may contribute. Resources should be made available to ensure the capacity development of the various sectors and professionals that bear responsibility for enforcing laws and implementing programmes. Adequate public funding should be allocated to non-governmental organizations and women’s groups, lead sources of expertise and services for survivors/victims for their work and contributions.

9. Are efforts focused on women’s empowerment and community mobilization?

Too often, there is a tendency to ‘supply’ policies and services, without adequately engaging the public through empowering approaches that enable people to ‘demand’ and access those services and to seek accountability. Real and lasting change to end violence against women and girls should be focused at the local and community levels, where acts of abuse occur and are too often tolerated. Strategies should empower women and girls to demand their rights to justice, protection and support; provide them with knowledge of their rights and their government’s obligations; and ensure collaboration with women’s centres and advocacy groups, as well as youth, men’s and other organizations committed to gender equality. Mass public education and awareness-raising campaigns on the issues, including through local and national media, are important elements. Community mobilization on gender equality and non-violence is essential to stopping violence against women and girls, especially among men, young people, faith-based and other strategic groups.

10. Are monitoring and accountability systems functional and participatory?

Regular and participatory government-led assessments at the national and local levels, in partnership with women’s and other civil society organizations, serve to ensure that policies and programmes work as intended and highlight opportunities for improvement. These assessments might include annual progress reports to parliament by sectoral ministries, the establishment of national and local observatories, independent oversight mechanisms such as ombudspersons, collaboration with the media to disseminate information on progress and shortcomings, and periodic evaluations of the enforcement of laws and implementation of programmes. Anti-violence policies and programmes should have clear targets and timelines so that their effectiveness can be measured and assessed. National monitoring efforts should also be linked to periodic State Party reporting obligations to the CEDAW Committee and other international treaty bodies.

These points were extracted from UNIFEM’s National Accountability Framework to End Violence against Women and Girls: 10-point Checklist (2009). The brochure and references can be downloaded in Arabic, English, French, and Spanish.

Mini Case Study: Systematic Data Collection by the United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice Bureau of Crime Statistics collates and aggregates data from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), one of the largest ongoing household surveys in the US, including data on homicides, domestic assaults, rapes, and sexual assaults; as well as from the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Uniform Crime Reports (URC), compiled from monthly law enforcement reports or individual crime incident records sent directly to the FBI or centralized state agencies, which include data on homicide, forcible rape and assaults. This represents some of the most systematic, comprehensive national level collection of data.

For more information on the National Crime Victimization Survey and to view the statistics, see the Bureau of Justice.

Monitoring and evaluating justice/legal sector initiatives at the local level

Even when unambiguous and appropriate laws and policies around violence against women are enacted in tandem with a clear commitment to human rights on the part of the government at national/central level, a number of barriers at the local level may prevent women from accessing meaningful justice and legal sector professionals from acting to prevent further violence.

Monitoring access to justice at the local level should include an assessment of:

- Appropriate infrastructure/ commodities for handling and interviewing victims.

- Clear policies and protocols for handling cases of domestic and sexual violence.

- Training for all personnel (justice, legal, security/police, etc.) around gender, violence against women, their legal obligations, and appropriate implementation of laws, policies and protocols.

- Development of referral networks and establishment of a coordinated response.

- Evaluation of initiatives could include assessment of reporting rates, case rates, conviction rates, women’s perceptions around the quality of services provided and whether their needs were met, barriers to access, and knowledge, attitudes and practices of police and other legal sector actors around gender and violence against women.

- Formal justice mechanisms are out of reach for a large number of women who have to depend on custom or informal justice systems to resolve problems, including incidents of violence. Women living in rural or remote areas with little access to urban centers may only have recourse to village chiefs or community-based policing initiatives, which requires adaptation and innovation of monitoring and evaluation methodologies and indicators.

CASE STUDY: Evaluation Findings of Informal Justice Systems in Melanesia and East Timor

These systems are much more accessible to the majority of people, and if supported with capacity building in gender equality and human rights principles they offer important opportunities for reducing violence against women.

Community-based justice, community policing, restorative justice, peace mediation and conflict resolution are being enthusiastically promoted by governments, donors and civil society organizations. However, these approaches can work against gender justice unless they include specific measures to level the playing field. In Vanuatu, training through the Vanuatu Women’s Centre Male Advocates Program has targeted village chiefs and other male leaders, with encouraging results. Chiefs who agree to abide by certain standards of personal conduct become part of the male advocacy network, attend refresher sessions and work with their local Committees Against Violence Against Women (CAVAWs).

East Timor has the best example in the region of monitoring women’s experiences with formal and informal justice systems, through the Judicial System Monitoring Program (JSMP). This programme was established in 2001 by an East Timorese NGO. Its reports have been used to press for reforms, including measures to increase election of women to local decision-making bodies (the suco [local government] and aldeia [village] councils) and the 2004 Decree-Law on Domestic Violence. Under this law, chiefs of suco councils are given duties to prevent domestic violence, support and protect victims, and punish and rehabilitate perpetrators. Continued monitoring of implementation will be used to inform the training for suco councils.

Strong local women’s rights organizations can be effective watchdogs of traditional and restorative justice systems. Some CAVAWs fulfill this role in Vanuatu, supported by their national organization, the VWC. The experience of some women’s community-based organizations in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea (e.g. Kup Women for Peace) shows this can be difficult and even dangerous work. Participating in wider networks, capacity-building for leaders and providing resources increase the chances of sustainability and success.

However, monitoring should not be delegated solely to NGOs. Justice systems should monitor and report on outcomes for women as a normal part of their operations.

Source: AusAid, Office of Development Effectiveness, Australian Government. 2008. Violence Against Women in Melanesia and East Timor: Building on Global and Regional Promising Approaches. Available in English.

Source: PATH, 2010.

Indicators

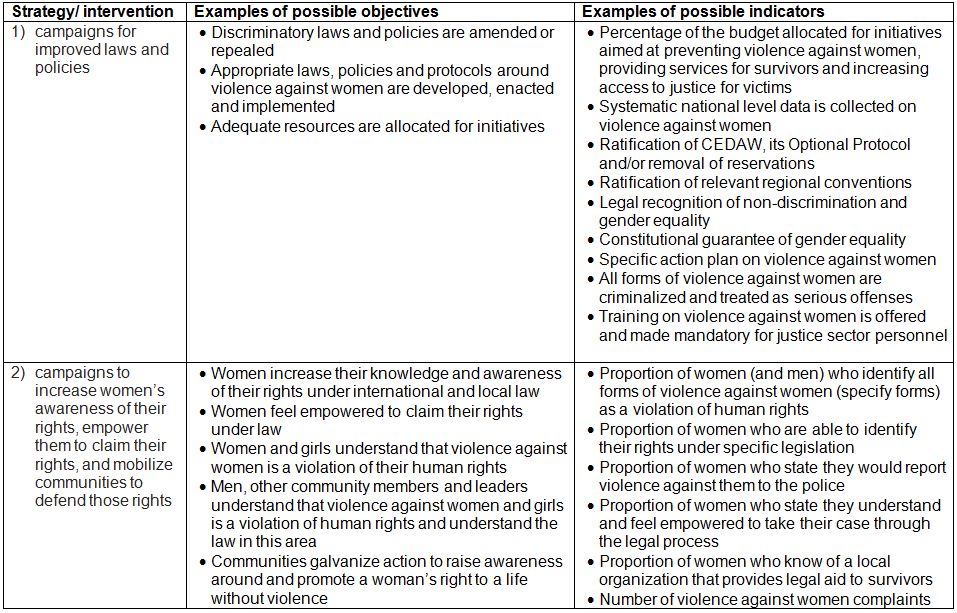

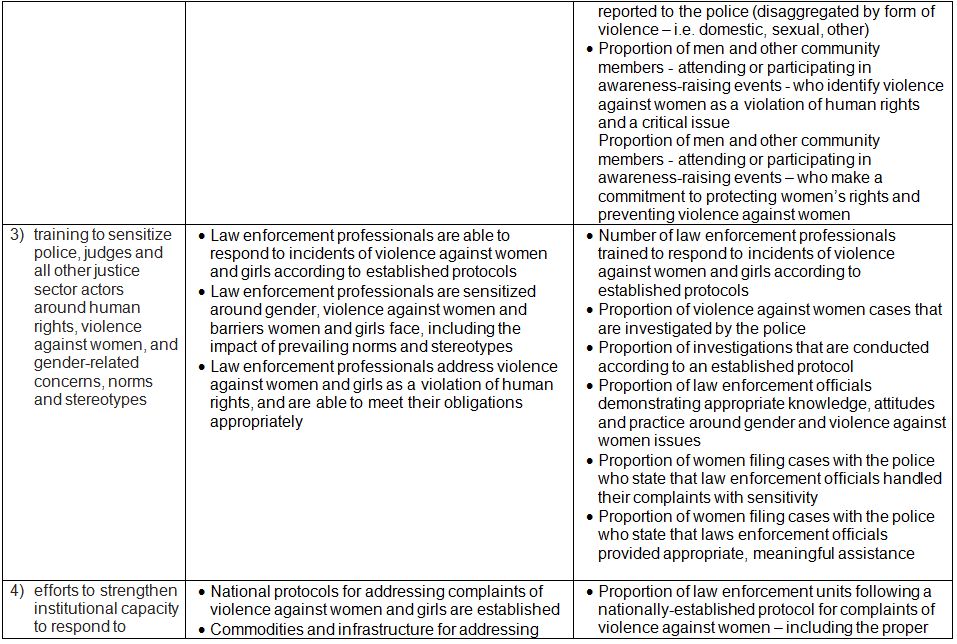

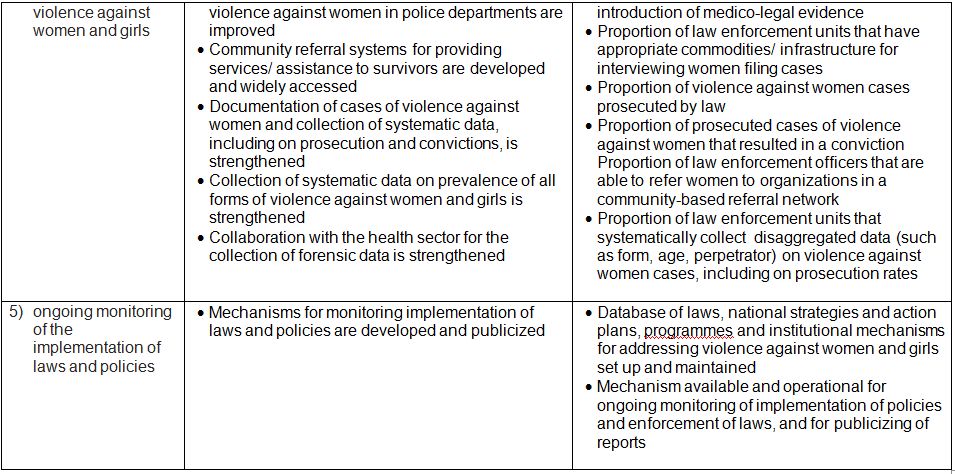

MEASURE Evaluation, at the request of The United States Agency for International Development and in collaboration with the Inter-agency Gender Working Group, compiled a set of indicators for the justice sector. The indicators have been designed to measure programme performance and achievement at the community, regional and national levels using quantitative methods. Note, that while many of the indicators have been used in the field, they have not necessarily been tested in multiple settings. To review the indicators comprehensively, including their definitions; the tool that should be used and instructions on how to go about it, see the publication Violence Against Women and Girls: A Compendium of Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators.

The compiled indicators for the justice sector are:

- Proportion of law enforcement units following a nationally established protocol for complaints of violence against women and girls (VAW/G)

What It Measures: This indicator measures the number of law enforcement units that handle VAW/G complaints using a protocol which is in compliance with nationally established standards.

- Number of law enforcement professionals trained to respond to incidents of VAW/G according to an established protocol

What It Measures: This output indicator tracks the number of law enforcement professionals trained to respond to VAW/G incidents using an established protocol.

- Number of VAW/G complaints reported to the police

What It Measures: This indicator measures how many VAW/G complaints were made to and recorded by the police during a specified time period.

- Proportion of VAW/G cases that were investigated by the police

What It Measures: This indicator measures the proportion of VAW/G cases that were followed up with a police investigation, during a specified time period.

- Proportion of VAW/G cases that were prosecuted by law

What It Measures: This indicator measures the effectiveness of the legal system by tracking the proportion of reported VAW/G cases that were prosecuted.

- Proportion of prosecuted VAW/G cases that resulted in a conviction

What It Measures: This indicator measures the effectiveness of the legal system by tracking the proportion of reported VAW/G cases that were both prosecuted and resulted in an actual conviction.

- Proportion of women who know of a local organization that provides legal aid to VAW/G survivors

What It Measures: This indicator measures the proportion of women who are aware of an organization that provides legal support to VAW/G survivors. Women may not need to know the specific organization, but should know enough about it to be able to access services if needed.

In addition to the previously noted internationally comparable indicators being developed to monitor States’ responses to violence against women, other illustrative indicators include:

The Report on Indicators on Violence against Women and State Response by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, (A/HRC/7/6, 29 January 2008) outlines a set of indicators, guided by human rights standards included in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women.

The Council of Europe’s Monitoring Framework (p. 47) that was established to assess the Implementation of and Follow-up to Recommendation Rec(2002)5 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the Protection of Women against Violence (EG-S-MV).

Illustrative monitoring and evaluation reports in the justice sector:

Different Systems, Similar Outcomes? Tracking Attrition in Reported Rape Cases in 11 European Countries (Lovett and Kelly, 2009). Available in English.

Responding to sexual violence: Attrition in the New Zealand Criminal Justice System (Triggs and Mossman, Jordan and Kingi, 2009). Available in English.

Implementation of the Bulgarian Law on Protection against Domestic Violence (The Bulgarian Gender Research Foundation and the Advocates for Human Rights, 2008). Available in English.

Judicial System Monitoring Programme (Women’s Justice Unit, Timor-Leste). Reports are available in English, Bhasa and Portuguese.

Tracking Rape Case Attrition in Gauteng: The Police Investigation Stage (Sigsworth, Vetten, Jewkes and Christofides/The Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, 2009). Available in English.

Tracking Justice: The Attrition of Rape Cases through the Criminal Justice System in Guateng (Sigsworth, Vetten, Jewkes, Loots, Dunseith and Christofides/The Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, 2008). Available in English.

Case Study: Monitoring Implementation of the 2005 Domestic Violence Act in India

The Women’s Rights Initiative of the Lawyer’s Collective in India has prepared several monitoring and evaluation reports on the implementation of the Protection of Domestic Violence Act which was brought into force in 2006. The objectives were:

- To map the infrastructure put in place by state governments to implement theAct;

- To collate the experience of stakeholders in using this infrastructure to provide relief to victims of domestic violence;

- To draw provisional conclusions on the influence of this infrastructure on the implementation of the Act.

In order to achieve its objective, the assessment sought to answer a series of questions, including:

- To what extent have the infrastructural gaps been fulfilled?

- What are the different approaches adopted by states in putting in place infrastructure to comply with the provisions of the Act?

- To what extent have states managed to develop a coordinated, multi-agency response mechanism as envisaged in the Act?

How is jurisprudence evolving under the Act?

- Has there been any change in the number of cases filed under relevant sections of criminal law (Section 498A)?

A two-pronged approach was adopted to gain an understanding of the functioning of the agencies put in place to implement the Act of 2005:

1. Primary data on the infrastructure put in place and the steps taken by the state towards effective implementation of the Act, collected from key departments of each state such as the Department of Women & Child Development and the Department of Social Welfare;

2. Selective state field visits to examine the manner in which the agencies are functioning on the- ground, through interviews with various stakeholders, including protection officers and service providers, representatives from shelters and medical facilities, women’s organizations, civil society organizations, NGOs and legal practitioners, state women’s commissions and legal services authorities.

To view the reports see:

Staying Alive: First Monitoring and Evaluation Reports on the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (Lawyer’s Initiative Women’s Rights Collective, 2007). Available in English.

Staying Alive: Second Monitoring and Evaluation Reports on the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (Lawyer’s Initiative Women’s Rights Collective, 2008). Available in English.

Staying Alive: Third Monitoring and Evaluation Reports on the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (Lawyer’s Initiative Women’s Rights Collective, 2009). Available in English.

Staying Alive: Fourth Monitoring and Evaluation Reports on the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (Lawyer’s Initiative Women’s Rights Collective, 2010). Available in English.

Staying Alive: Fifth Monitoring and Evaluation Reports on the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (Lawyer’s Initiative Women’s Rights Collective, 2012). Available in English.

Staying Alive: Sixth Monitoring and Evaluation Report on the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (Lawyer’s Initiative Women’s Rights Collective, 2012). Available in English.

Illustrative Tools:

Tool for Assessing Justice System Response to Violence against Women, A Tool for Law Enforcement, Prosecution and the Courts to use in Developing Effective Responses (The Battered Women’s Justice Project and National Resource Center on Domestic Violence, 1998). This assessment tool was created for communities in the United States to use in developing effective responses by law enforcement, prosecution, and the courts to cases of violence against women, but is also a resource for monitoring those responses. The tool includes a set of response checklists that highlight key elements of good practice, describe the basic roles of law enforcement, prosecution and the courts in responding to violence against women and show where agencies coordinate and collaborate with other agencies and advocacy programmes; and also highlight any gaps to assess progress and areas for improvement in the response. Available in English.

Court Monitoring Programs (WATCH, Minnesota, USA). This site provides information on the purpose of court monitoring programmes, instruction on how to establish them, what to monitor and how. Available in English.

The Women’s Justice Center (Centro de Justicia para Mujeres) developed a form for evaluating police response to rape and sexual assault. The form was designed for use by victims, advocates and law enforcement officials to help assess police response to cases. The questions are divided into three parts: Initial Police Response, Victim Interview and Investigation Follow up. The majority of questions focus on the police interview of the victim, as well as the victim’s comfort and safety during the investigation process. Available in English and Spanish.

The CEDAW Assessment Tool: An Assessment Tool Based on the Convention to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (American Bar Association, Central and East European Law Initiative, 2002). Available in English.